A twitter follower asked me why NATO adopted the 5.56 over the 7.62 cartridge. This led to a “short” answer:

I’ll be explaining the longer answer over a number of posts. The long answer giving context from 20th Century infantry tactics and logistics concerns. It’s an interesting explanation of how warfare has become decentralized, but with trade offs at every step of the way.

In this first post I will look at how infantry units evolved during World War One, simultaneously increasing the complexity of an infantry platoon while setting up the calibre problem

Paying the Bills

A reminder that I have a paid tier. It includes all YouTube videos being released at least a week early and every second Substack post is for paid subscribers only. Click on the link to join them and get access to Episode 9 of the Ukraine War series (available to the public on July 2nd).

Pre-World War One - The Uniform Battalion

The main manoeuvre element in 1914 was the battalion. It had not changed much in structure since Napoleonic times, with the major change being upgrading the standard infantry arm.

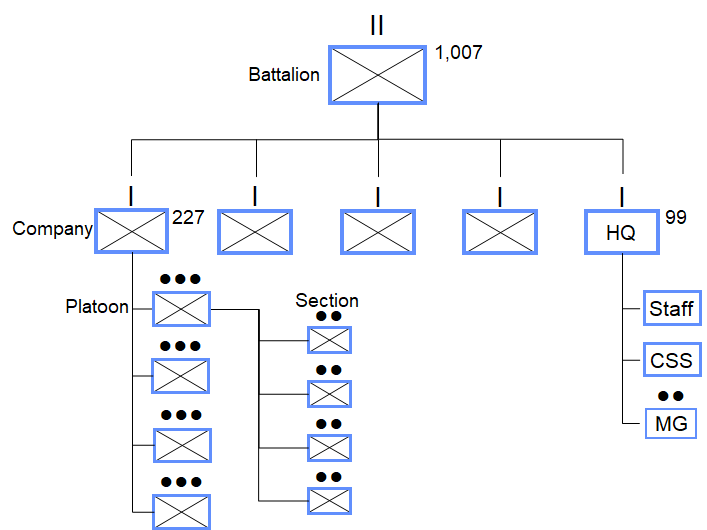

In 1914 the infantry battalion of the British Army this consisted of:

30x officers armed with revolvers

2x Vickers machine guns (heavy machine guns by modern parlance)

977x non-commissioned soldiers with Lee-Enfield rifles

They were organized into four rifle companies and a headquarters. The headquarters included cooks, drivers, medical staff, staff officers and the four machine guns. However, this entire support and leadership element was less than 10% of the battalion.

Ninety percent of the battalion’s strength was in the four infantry companies, which consisted of six revolver armed officers and 221x riflemen. This means 88% of the infantry battalion consisted of riflemen in the infantry companies.

The company was further divided into four platoons and those into four sections of about a dozen riflemen.

How the Uniform Battalion Manoeuvred

In terms of manoeuvre in combat the battalion would advance in rushes. Soldiers would be prone, or as close to prone as possible while still being able to see the enemy (in tall grass for example troops would kneel). On command one group would suppress the enemy with rifle fire while the other group stood up, sprinted forward and then went prone.

In this film from the Eastern Front in 1915 we see a German company firing on the enemy. In the background another Company advances in a rush, then the foreground Company advances in a rush while supported by the first company. Note also the spacing of 2-3 meters, as this was the standard in the first year of the war.

If terrain was open the battalion would advance in company rushes. That is one company would fire while the other advanced in a rush, with the two remaining companies forming a reserve in a second wave. If the terrain was too complex and closed to make this practical platoons would advance under company control. There was no provision for a section level attack (the American term is squad) and so the section largely existed for better administrative control of the soldiers when not in combat.

For firepower everything revolved around the rifle. The British Lee-Enfield had a 10 round magazine fed from stripper clips. It fired a .303 (7.7 x 56mm) cartridge. It was effective with aimed shots up to almost 1km and in volley fire as a large target (like a mass of African tribal warriors) at up to 3km. Trained soldiers could shoot 15 well aimed shots per minute.

Today the .303 and similar cartridges are considered overpowered for anything but hunting larger game, medium machine guns, designated marksman rifles and sniper rifles. Examples of current weapons using this category of cartridge include the Dragunov and FN MAG.

Rifles and Machine Guns at the Outbreak of World War One

In 1914 every army was equipped with a broadly similar weapon with a similar cartridge. Specifically a magazine fed bolt action rifle with a cartridge over 7x50mm. This type of cartridge was hard to control, was painful to fire more than a few rounds and was optimized for ranges over 400m. This overpowered cartridge makes sense given that most European combat experience for the 50 years leading up to World War One was on the plains of Africa, where engagements over 1km were common.

Every army also had two heavy machine guns per battalion. Their main role was defending the flanks or providing suppressive fire from a high feature during the attack. They were too heavy to be moved with the advancing infantry, so they typically kept the same position through the entire attack. In this sense they were closer to light artillery than our current concept of a machine gun.

The machine guns of 1914 used the came cartridges as that nation’s infantry rifle. There was no conflict between the cartridge requirements of an infantry rifle and the machine gun. They both needed a full powered rifle cartridge that could easily handle ranged over 500m.

Lessons from the First Month of World War One

The bloody slaughter of the first few months of World War One is well known by anyone who has read at least some military history. The first month of the war saw a mobile campaign on the western front. During that time the French, British and Belgians suffered about 380,000 casualties while the German army in the west suffered about 325,000 casualties. This amounted to almost 24,000 casualties per day.

However, the image of this period is overly mythologized. The main killer in 1914, as it was throughout the entire war, was artillery. The second was probably rifle fire followed by machine guns, but we lack good statistical data on the cause of casualties in the first month of the war.

To explain why we need to look at infantry tactics and enfilading fire. Below is the earliest known image of combat, taken in 1870 during the Franco-Prussian War.

If we zoom in on the advancing Prussians we can see an example of open order infantry.

They are a little too close together. Probably a mixture of open order being a fairly new development and the tendency of inexperienced troops to bunch up. Open order should be 2-3m apart, with this clip from the earlier German video being a better illustration:

Open order was considered the best infantry formation in 1914, apart from the French who still predominantly used closed order (1m spacing). When taking rifle fire from the front closed order is not as suicidal as it seems. At closed order an aimed shot that misses a soldier is unlikely to hit his comrade to the left or right, but the return fire will be more concentrated.

At the open order soldiers are better able to select cover, and machine guns sweeping left to right in 5 round bursts (their ideal rate of fire) are unlikely to hit more than one soldier.

However, the open order tactics of 1914 proved suicidal due to two factors: field artillery and enfilading machine gun fire.

The Bloodletting of Artillery

When fighting in open terrain the most lethal weapon was field artillery. Field artillery is a light gun (at this time usually below 90mm) that predominantly fired shrapnel shells and was meant to fight on the firing line with the infantry.

The best type of field artillery in 1914 was the French 75mm. It could fire ** shells per minute. When a shell hit the ground just in front of advancing enemy infantry it created a lethal spray of shrapnel 35m wide and 50m long. Consequently, the entire line of infantry from this photo could be killed or wounded by a single 75mm shell.

Under these circumstances open order was insufficient protection from field artillery, and operating in closed order was near suicidal. The only viable protection was to dig trenches. That way the shell would impact the ground and spray shrapnel over the soldier’s heads instead of into their bodies.

The continuous line of trenches through France and Belgium greatly limited the effectiveness of Field Artillery. The Field Artillery also took devastating losses during the initial mobile stage of the war. Occupying the firing line with the infantry may have been viable in the Napoleonic wars against muskets, but against modern rifles it was not.

Therefore as the trench stalemate settled in the dominance of the Field Artillery faded. Artillery now fired indirect (over the horizon), preferably on a high angle that could drop into trenches and with a large explosive charge to collapse trenches and destroy barbed wire. This required heavy artillery firing high explosive shells rather than field artillery firing shrapnel shells.

Artillery shifting from a primarily direct fire to indirect fire weapon also made it ineffective in the offensive. Without direct line of sight artillery relied on spotters. While on the defensive they could communicate with the guns thought telephone, but radios in that era were too bulky and ineffective to be brought along with advancing troops.

In fall 1914 as the field artillery faded in prominence the machine gun also rose to the forefront due to its suitability to trench warfare.

The Rise of the Machine Gun

While machine guns were not particularly more powerful than rifles firing to the front of an advancing enemy, they were much more deadly when dealing e

enfilading fire. Enfilading fire is fire directed across a unit’s axis of advance. This negates the dispersion from an open order formation. For example, here is the photo of a German unit advancing at open order in 1914 from the front:

Versus from the flank (along its axis of advance). Clearly a 5 round burst will bring about much more devastation in the second image.

If you look at just about any World War One movie they portray waves of infantry rushing towards machine guns that are firing strait at the enemy’s front. This is not how machine guns are employed in a prepared defensive position. Ideally there is a C shaped trench network, with a pair of machine guns at each tip.

The machine guns cover the kill-zone with enfilading fire and protect each other. If the enemy assaults machine gun #1 then it’s protected by machine gun #2, not by machine gun #1. Ideally the machine guns are placed so they cannot fire in self defence towards the enemy’s front. If you can shoot at the enemy then they can shoot at you, so setting up a protected ‘keyhole’ shot in enfilade means the machine gun is protected from enemy fire in all but the most favourable conditions.

The Solution to Trench Warfare

By 1915 it was clear to the major combatants that their armies needed to be totally restructured to break the trench stalemate. For artillery they needed a lot more heavy artillery firing high explosive shells. This is a separate story, but it took them until late 1917 to achieve this change.

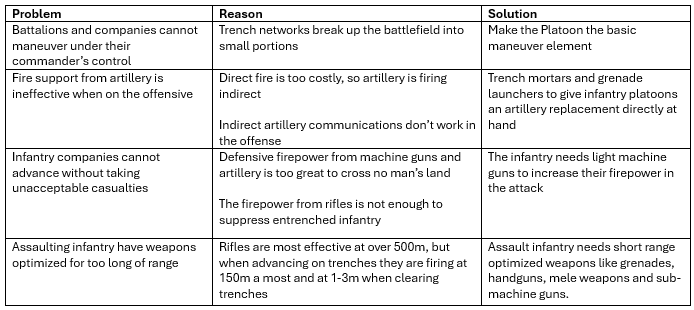

Regarding the infantry they had the following problems with associated solutions:

Looking at the doctrine and pamphlets most military establishments deduced these solutions by late 1915. Similar to the heavy artillery issue it took until nearly the end of the war to implement.

However, these solutions created their own problems and required insoluble trade offs that are still a conundrum for modern armies. That story will play out in the next article.

![r/HistoryPorn - Franco-Prussian War, Battle of Sedan, 1 September 1870. This image is considered to be the first actual photograph taken of a battle. It shows a line of Prussian troops advancing. The photographer stood with the French defenders when he captured this image. [1459x859] r/HistoryPorn - Franco-Prussian War, Battle of Sedan, 1 September 1870. This image is considered to be the first actual photograph taken of a battle. It shows a line of Prussian troops advancing. The photographer stood with the French defenders when he captured this image. [1459x859]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!XuUP!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fb3a26032-bba5-455b-bf6f-412801378d81_640x376.jpeg)