In the last episode we determined that America needs to assemble an invasion force of 27-35 combat brigades for an invasion of Iran. They are unlikely to have more than four brigades provided by allies, so 23-31 of those brigades need to be American. This is a force commitment about 50% larger than the 2003 invasion of Iraq, which occurred when the US military had less overseas commitments and was 10% larger.

The US military is capable of deploying 22-31 combat brigades for an invasion of Iran, but only through a callup of National Guard and Reserve personnel at about double the peak reached during the War on Terror.

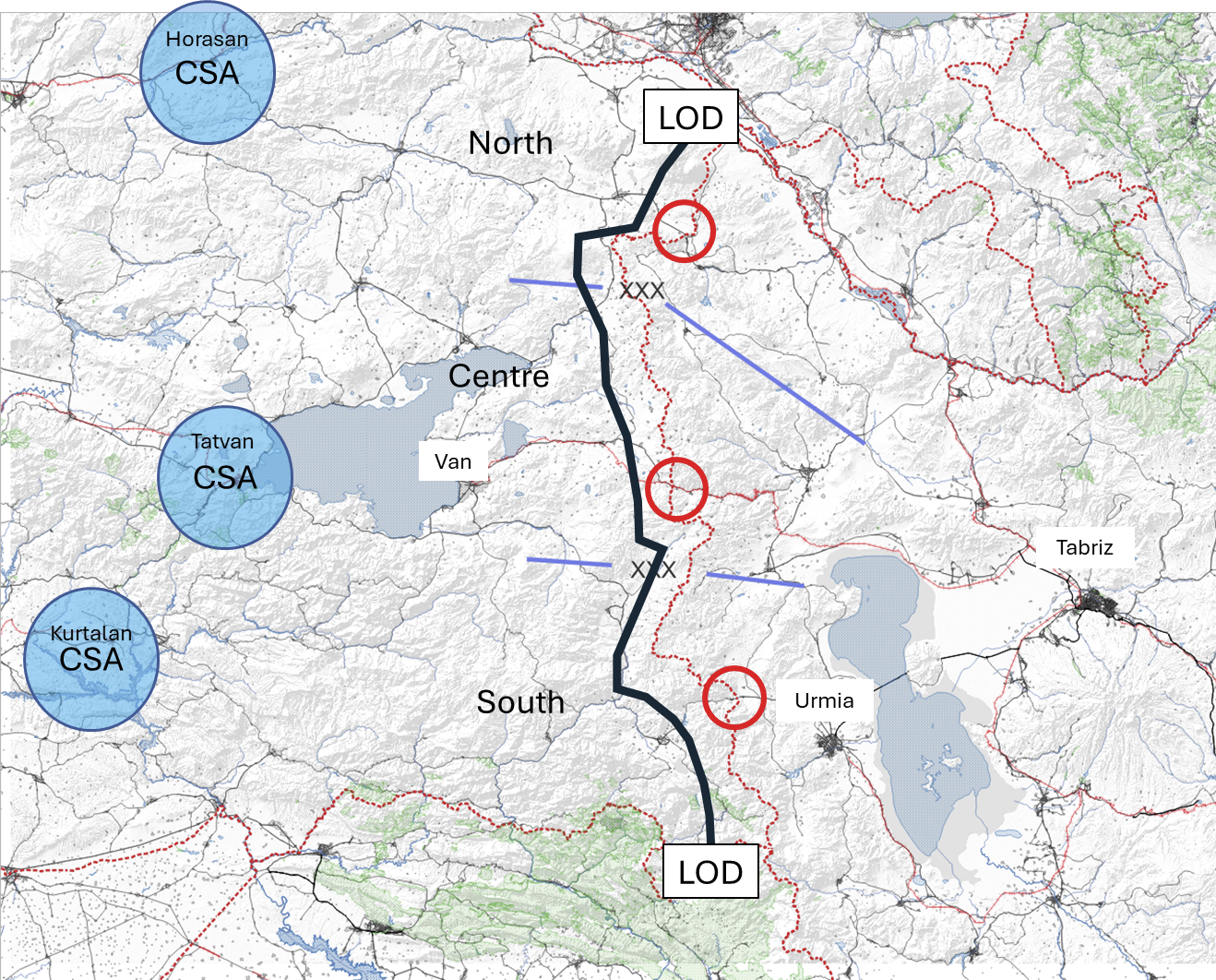

In this post we will look at the terrain along the possible invasion routes out of Turkey and Armenia.

Politically Viable Invasion Lines of Departure

Iran shares a border with Armenia, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq and Turkey. The diagram below (which isn’t even trying to be to scale) shows Iran in the centre and Iran’s neighbours in the middle ring.

NAR is an Azerbaijani enclave in Armenia.1

The outer ring of hexagons shows which sphere of influence the country falls under. In this case I define sphere of influence as whether the US is able to use that country as a line or departure for an invasion, and it not what other power is capable of stopping the US from doing so.

Applying these criteria the US is able to invade Iran via Iraq, Turkey and possibly Armenia. Being the world’s uncontested naval power America can also invade via the Persian Gulf, if they are willing to fight their way through the Strait of Hormuz.

One can endlessly argue what if scenarios for political questions like which countries the US could use to mount an invasion of Iran. This post will simply assume America’s options for an invasion of Iran are Iraq, Turkey (with an option of a supporting advance out of Armenia) and the Persian Gulf.

Of note Qatar, the UAE and particularly Kuwait are countries in the region containing significant American logistical infrastructure.

Political Considerations for Turkey & Armenia

Despite recent tensions Turkey remains a NATO member and a key US ally in the region. Armenia is caught between the US and Russian spheres of influence. In order to give an optimistic view of this invasion corridor I will assume American diplomatic pressure allows full access to Turkish and Armenian territory and infrastructure for an invasion of Iran.

For Turkey this would probably involve a deal to suppress the Kurds, as the border region between Iran and Turkey is Kurdish.

Gaining access to Armenia would mean making a deal with the Russians to allow placement of US forces so close to one of Russia’s contentious border regions and a large part of her oil reserves. All this is to say I am hand waiving some very significant diplomatic problems.

Invading Iran from Turkey

At first glance Turkey seems the ideal country from which to invade Iran. It is a NATO member with nearly European level of development. It shares about 520 km of border with Iran. However, there are serious supply issues in Turkey and terrain issues on the Iranian side of the border.

Logistic Support Up to the Corps Service Area (CSA)

The logistics plan would involve landing units and supplies by ship and then moving it inland by rail to a Corps Support Area (CSA). The best port for supporting the LOD is Mersin in the south. This is Turkey’s second largest port and it handles 3.3 million shipping containers (TEUs) per year. This is roughly on par with Huston Texas, and more then enough capacity to support the US invasion force.

After offloading from Mersin units and supplies would be sent 800 km east by rail to Corps Support Areas. The rail network in eastern Turkey is sparse, entirely single track and has limited redundancy (that is it spreads out like spokes of a while rather than like a grid). It being single track is not a major issue. The volume of fright that can be moved by rail versus by truck or air is mind boggling.2 The sparseness and lack of redundancy means the railway network is very vulnerable to disruption by Iran’s drones and long range missiles. A single successful strike on an unoccupied stretch of track could isolate a CSA from rail connectivity for several hours.

To some extent the railway links to the CSAs could be supplemented by trucks, but the roads in eastern Turkey are also sparse. Even the US military does not have the truck lift to link a sea port to CSAs that are about 800 km away.3 Local civilian trucking companies would need to be contracted. If the Iranians destroyed a few dozen of these civilian trucks these contractors would probably cease to offer their services.

Therefore movement up the CSAs is easily disrupted if even a small percentage of Iranian drones and precision missiles penetrated the air defence network.

Logistic Support up to the Line of Departure (LOD)

The starting point for a military manoeuvre is called the Line of Departure, or LOD. In practical terms it is where elements line up in the direction of the enemy before starting their advance. In this case the LOD would be a line drawn on the American’s maps along the Iranian border a few kilometres Turkey and Armenia.

The border between Turkey and Iran is about 520km long, but there are a lot of little folds and zigzags stretching that distance out. The LOD would have much straighter lines, making it about 350 km long.

A CSA is ideally 180-190km from the LOD. Horasan in then north and Tatvan in the centre are both about 180 km from the LOD. In both cases the road network from the CSA to the LOD is a sparse network of mountain roads.

In the south the railway line stops at Kurtalan, about 260 km from the LOD. The road network between the Kurtalan CSA and the LOD is even worse. In terms of distance the southern portion of the LOD could be supported by a CSA in Van, but this is far too close to the LOD at 70 km. A CSA that close to the LOD would be vulnerable to too many of Iran’s missile systems. However, the southern CSA could be moved to Van after the force in the centre pushed the Iranians back about 100 km from the border.

With these logistical headaches identified we can now move onto the most serious tactical constraint: there are only three road crossings of the border between Turkey and Iran.

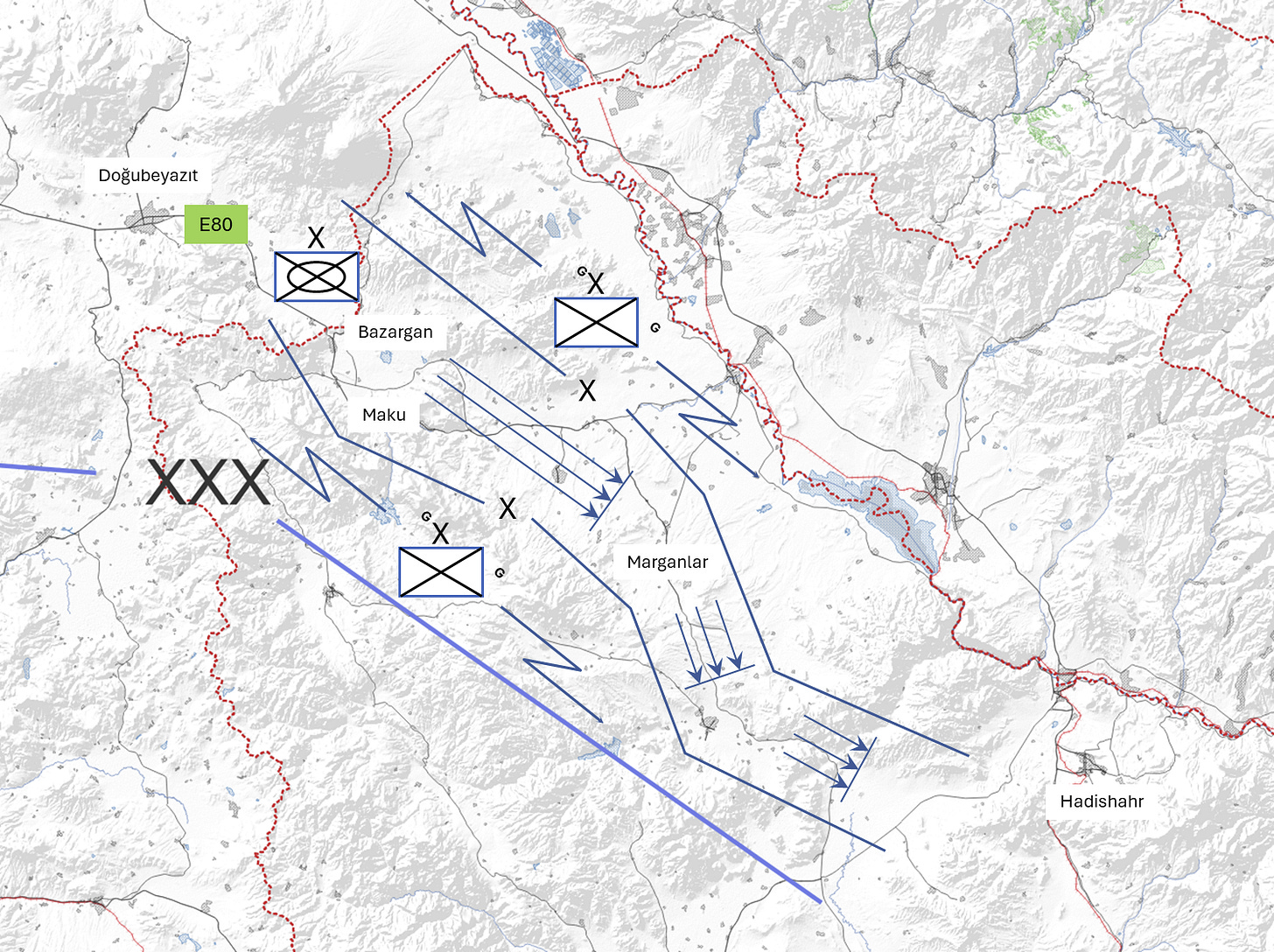

Invasion Route - North

The Northern invasion route has fairly promising terrain for offensive operations, but a poor road network. The E80 highway runs from the LOD at Doğubeyazıt, though the border crossing at Bazargan and then onto the intermediate objective of Marganlar. The frontage of this route varies from 50-66 km, which is about the frontage of two divisions.

The highway itself is a fairly good road. It is always paved and multi-lane. In some locations is it a divided highway.

There are two roads at the Bazargan border crossing, and three places in the town where roads on the Turkish and Iranian sides could be constructed within a day or two. The area around Bazargan with these roads is about 8 km wide, which is the right frontage and number of roads for a US Brigade Combat Team advance. The highway E80 corridor after Bazargan is similarly build up enough to support a US Brigade Combat Team advance to past Marganlar.

However, for the entire rest of the border there are only dirt roads that do not link across the border and are separated by a stream or the ridge-line of a steep hill. Past the borders the roads are too sparse to support an advance by anything except dismounted infantry fighting on foot with minimal artillery support.

So while the Northern route has a frontage large enough for two divisions (which would be four brigades up front) the road infrastructure only allows a single brigade to advance down the E80 highway corridor. This Thunder Run down the E80 highway would need to be protected by brigades guarding each flank of the advance.

However, this guard force would be operating with almost no roads. They would need to be moves and resupplied mostly by helicopter. These types of operations are resource intensive and inherently riskier. Therefore though the Northern invasion route would be a risky

Invasion Route - Centre

The North and Centre routes are very similar. There is only one crossing point at the border, in this case the D300 highway runs from Kapıköy at the border. It is a similar quality road to the E80 highway in the North, but it has a railway line running parallel.

However, for the first 50 km past the border there are dense mountain slopes and the D300 highway is the only road running east to west along the axis of advance. This means for the first 50 km any mechanized force would need to advance with a company frontage (about 10% the size of the brigade width of advance in the North.

Advancing the first 50 km down the D300 highway would be a difficult and risky operation. In a situation reminiscent of Operation Market Garden, a Corps level advance would depend on progress down a single road hemmed in by excellent defensive terrain.

After this 50 km company wide corridor the terrain opens up around Khoy and Salmas. There are three brigade sized corridors:

Heading North East to Jolfa, which could allow an encirclement of Iranian forces on the Northern route;

East to Marand, which is a large town but otherwise not a significant objective; and

East towards Tabriz. Tabriz is a city and a more significant transportation hub. This includes the railway running along the D300 highway, which could allow the CSA to relocate for future operations.

Therefore the Centre route is very risky for the first 50 km, but then opens up in terms of the terrain and number of roads to allow an advance by several brigades.

Invasion Route - South

The southern route is the worst in terms of roads, worthwhile objectives and good offensive terrain. Like the other two routes, the border crossing routes consist of one good highway, in this case the D400 which crosses at Esendere.

Next there is a 30 km long corridor that is initially battalion sized, but quickly becomes a company sized advance through a mountain road until Azadegan. At this point the terrain opens up and there is a decent road network, but 5 km later you would be fighting through the city of Urmia. As discussed in other videos, fighting through a city should be the last resort. You should always encircle a city if possible. However, the road network in this area means a US invasion force can only fight through Urmia.

Assuming the US forces on this route successfully fight throughout the company wide corridor, and then fight an urban battle through Urmia, the manoeuvre options then become somehow worse.

East of Urmia is Lake Urmia, so the only useful direction to advance is south. This advance involves a 50 km long company wide corridor to Oshnavieh and a 65 km long company corridor to Naqadeh. The advance must then turn east to fight through company to battalion wide corridors for another 40 km to Miadoab, where the terrain finally opens up.

However, the railways in this area don’t link back to the Turkish border, so to use this transportation infrastructure US forces need to turn North and fight through another 120 km of large towns, mountains and some open terrain to link up with forces on the centre route at Tabriz.

Armenia

Armenia shares a short border with Iran, as there is an Azerbaijani enclave along most of what would otherwise be the Armenian-Iranian border. Operations out of Armenia would be limited due to the narrow border and poor transportation infrastructure.

Logistic Support Up to the Corps Service Area (CSA)

The only way for the US to transport bulk supplies into Armenia is via the Turkish railway network. The single track line that supports the northern Turkish CSA at Horassan carries on into Armenia.

The railway stops near Ararat, which is about 200 km from the LOD. This is close to the ideal placement of a CSA, but given the poor quality of the roads leading to the LOD they would ideally be closer.

Logistic Support Up to the LOD

The route between the CSA and the LOD is along more of a country back-road than a highway. For almost the entire route there is only a single road, with no alternate routs, even accounting for dirt roads.

The LOD is only about 30 km, but the only road allowing movement for supplies along the LOD runs within 500 m of the border. Consequently almost the entire invasion force would need to be held 30-50 km to the rear until just before the beginning of hostilities.

Advancing Past the LOD

This may sound repetitive, but there is only one road crossing of the border between Armenia and Iran. The border is along the Aras river, which is less than 100 m wide, so engineers could quickly construct other bridges.

However, there is only one road leading away from the border into Iran. Similar to the road leading to the LOD, it is a paved dual lane mountain road. Besides this one road this region is remote and undeveloped to an astounding degree.

All that can be accomplished here is a battalion level seizure of the border crossing as Nordooz, followed by a slow advance up a 30 km long company sized lane towards Kharvana. Raids could also be conducted on foot across the rest of the border, but these raiding parties would need to be supplied by helicopter or mule.

After Kharvana there are sometimes two roads to advance along, but the terrain is the same for about 200 km until you arrive at Tabriz.

A Possible Manoeuvre Plan

If I were ordered to develop some kind of plan for an invasion of Iran via the Turkish border I would use the centre route to seize the city of Tabriz and encircle Iranian forces in the north.

In the centre an airborne brigade would seize the eastern end of the company wide corridor on highway D300 near Khoy. This is a risky operation, but it would prevent Iran reinforcing the defenders while a mechanized brigade clears the D300 highway and links up with the airborne defenders. Light forces in Armenia and in the south would fix Iranian units through probing attacks. In the north a mechanized brigade would advance down the E80 highway with two light brigades as flank guards. This would ensure the buildup of a large Iranian defensive force around Marganlar.

Taking the D300 corridor and Khoy would create an exposed salient. This salient would be protected through brigades blocking counter attacks out of Salamas and Marand, as well as the airborne brigade guarding the exposed northern flank. Mechanized brigades would then breakout to secure Trabiz and Jolfa. Tabriz is an important objective as a transpiration hub. Seizing Jolfa would encircle the Iranian defensive force around Marganlar.

Including the need for a reserve and other miscellaneous tasks not on the map, this operation requires 12-15 brigades, which equates to 4-5 divisions or an over-strength Corps.

To place this manoeuvre plan in the context, the map below shows the part of Iran it would seize shaded in blue.

On the positive side this is an area larger than Crimea. On the other hand it is less than a quarter of the way to Tehran. The terrain only becomes more favourable to the defender as you push further into Iran on this invasion route.

Conclusion

America does not have good options for invading Iran on the Turkish and Armenian borders. Although Turkey is a NATO ally with a near European level of development, that development drops off dramatically as you move east in the country. The Turkish and Armenian borders with Iran are on mountainous excellent defensive terrain. The road and rail networks are full of choke points and single points of failure, ensuring that Iran only needs a small fraction of their missiles and drones to survive the US air defence system in order to create critical logistic disruptions.

The most viable manoeuvre plan I can identify uses 12-15 brigades while not accomplishing much in terms of wider war goals against Iran. I would not recommend this approach.

However, there are still options on the Iraqi border and on the Persian Gulf to be examined in the next post. Perhaps these areas hold the elusive keys to success.

NAR refers to the Azerbaijani enclave that occupies most of what would be Armenia’s border with Iran.

During Operation Desert Storm Divisions averaged 19,000 tons of supplies per day. At this rate of consumption the entire US Army and Marine Corps would consume about 443,000 tons of supplies per day. A single railway line can operate about 50 trains per day, moving about 500,000 of tons of supplies.

This is the linear distance (or “as the crow flies”) Due to the mountainous terrain the driving distance would be almost twice as long.

Thank you for giving us some insights into this. We are witnessing history play out in the middle east and we need a framework to make sense of it all.