In the last post we concluded America’s viable starting points for an invasion of Iran were via Turkey, Armenia, Iraq and the Persian Gulf. We then looked at the invasion routes out of Turkey and Armenia, concluding these were not viable due to poor transportation infrastructure and excellent defensive terrain.

In this post we will look at the invasion routes via Iraq.

Invading Iran from Iraq

There could easily be several posts on the political issues related to staging an invasion of Iran out of Iraq. The United States spent eight years in Iraq fighting a counter-insurgency campaign before withdrawing in 2011. They then returned for 2014-21 to fight ISIS.

Iraq and Iran are historically enemies, but during the insurgency and the fight against ISIS Iran gained considerable influence within Iraq. I have heard several commentators I respect state Iraq is more in Iran’s sphere of influence than in America’s.

I will assume a diplomatic solution allows American forces to stage an invasion out of Iraq. However, this move would require a considerable force be held back in Iraq for rear area security.

Logistic Support Up to the Corps Service Area (CSA)

Due to the legacy of the War on Terror the US has a lot of military infrastructure near Iraq. There are significant logistics related bases and airfields in Kuwait, Qatar and the UAE. The US Army also maintains the prepositioned equipment for an Armored Brigade Combat Team in Kuwait.

To support an invasion of Iran the US would probably establish CSAs in Kuwait and in the Northern Iraqi city of Erbil. However, almost all of America’s ability to move units and supplies into these CSAs depends on the use of the Persian Gulf as a shipping route.

The scale of supplies needed by a modern army can only be provided over long distances by shipping and railways. Trucks can only be used for relatively shorter distances. As discussed in this video asking what Russia could have done with Hostomel airport, air transport can only fulfill a fraction of supply needs.

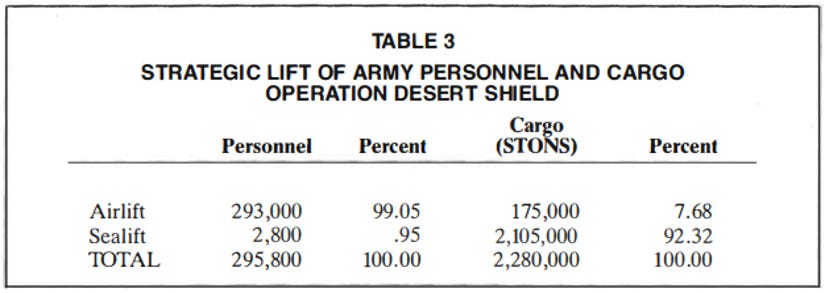

As another example, during Operation Desert Shield almost all the personnel were flown into Saudi Arabia, but over 92% of the cargo came by sea-lift.

Operation Desert Shield also showed the limitations of long range logistics via truck. Supplies were offloaded at Saudi harbours in the Persian Gulf and either moved up the coast toward the Kuwaiti border by truck or by rail inland to Riyadh.

At that time American Corps Service Areas (CSA) were ideally about 140 km from the forward units.1 During Desert Shield the CSAs were 400-950 km from the forward units. This resulted in significant supply issues for units that were in a defensive posture not even involved in war-fighting.2 Coalition forces were only able to transition to offensive operations against Iraq, which required a much larger scale of supplies, by:

Building up pre-positioned stocks over a period of 5 months; and

Increasing their heavy truck holdings from 250 to 2,650 through coalition partners and local contractors.

Even so, the report to the US Senate oversight committee noted the logistics system ran on a shoestring.

Kuwait and Iraq have harbours capable of supporting US operations in Umm Qasser and Kuwait City. There is a railway line from Umm Qasser to Erbil, but this port is right on the Iranian border. However, these harbours are too close to Iran to be used as main ports.

American also doesn’t have viable options other than using the Persian Gulf Ports. The Iraqi railway network only connects to Syria. Given they were recently conquered by an ISIS affiliated rebel coalition, flat bedding Abrams tanks by train through Syria is not an option. There are plans to build a railway connection to Turkey, but this is optimistically scheduled for completion in 2030.

Saudi Arabia has a railway project linking the Red Sea to the Persian Gulf ports. This hypothetically would allow logistic support of the Kuwait CSA without needing to use Persian Gulf Ports, but this project is also scheduled for completion in 2030. Even then supplies for the Erbil CSA would need to be moved by truck to the Iraqi railway network, because the Kuwaiti and Iraqi railway networks are not linked. This is for diplomatic rather than practical reasons, so the rail networks will not be connected in the near future.3

Therefore the logistics plan for an Iranian invasion out of Iraq would involve CSAs in Kuwait and Erbil, with supplies offloaded in Saudi ports right across the Persian Gulf from Iran. Supplies would moved by truck to the Kuwait CSA and to rail-heads in southern Iraq, where they would be moved up to the Erbil CSA.

This is not an efficient or secure logistical network. It would involve significant use of local contractors. For obvious reasons America relying on local Iraqi contractors in this era has inherent risks. The Iraqi railway network is also perilously close to Iran. For most of the route to Erbil there is only a single routing option. So similar to the Turkish railway network, a few Iranian drones and cruise missiles getting through American air defences would cause significant disruption.

Logistic Support up to the Line of Departure (LOD)

Fortunately the situation for movement between the CSA and the LOD is much better. Iraq has a moderately good road network for the south central to south eastern part of the country where most of the invasion force would be located. This is also an area of flat hard-pack desert, so the trucks in logistics units can travel cross country if needed. It creates greater wear, increases fuel consumption and decreases speed, but it can be done.

The road network in the central part of Iraq is more sparse, but the terrain is still hard-pack desert. In the north there are more mountainous and forested terrain, but the road network here is acceptable for movement up to the LOD.

Invasion Routes - Historical

The only invasion of Iran since WW2 was the Iran-Iraq war of 1980-88. Tellingly, almost the entire conflict was fought over the limited open terrain in the South-west of Iran, with almost none of the fighting taking place on mountainous terrain. This makes sense, as Iraq had a smaller, but more mechanized army where fighting on open terrain was to their advantage.

From 1981 to 1988 the war was an attrition trench warfare conflict that has garnered many comparisons to WW1. However, the was began in 1980 with an Iraqi attempt at an armoured manoeuvre campaign. The map below shows the manoeuvre campaign plan and outlines the actual gains made in blue.

In the centre of the country two infantry divisions advanced 5-20 km into Iran before being stopped at the beginning of the mountainous terrain. This force had only been intended as a diversion to fix Iranian units.

The main effort was in the south; seizing the petroleum handling port of Bandar and encircling Ahvaz. The left hook of the encirclement was two armoured divisions advancing out of Basrah. The right hook was an armoured and mechanized division advancing out of Um Qasr. The right hook was tasked with seizing petroleum handling ports near Bandar and then both hooks would link up near Ahvaz.

The southern force advanced 20-50 km into Iran before the offensive ground to a halt. They managed to cut off some of the petroleum ports, but otherwise failed all their operational and strategic level objectives.

It is difficult to tell how much can be learned from the Iran-Iraq war. Both armies fought at well below their expected effectiveness. Iran had recently purged most of the experienced officers from the army. The Iraqi invasion was micromanaged by Saddam Husain, who’s only education or experience before becoming a politician was dropping out of law school.

However, there are three key lessons from the Iran-Iraq war that apply to a potential US invasion:

The fighting was concentrated in the limited open terrain in the south-west. This is the area most suited to offensive operations and it contains most of Iran’s petroleum industry; and

Despite the country being in disarray, the army demoralized and the new Islamic government not having fully secured power, Iran mounted a determined and persistent defence to a foreign invasion.

Invasion Route - South

The terrain in the south is good to excellent for offensive operations. There are a number of canals, rivers, villages and cities, but not enough to anchor a good linear defensive line. Like the border with Turkey, there are not many roads crossing the border. However, there are good road networks on both side of the border and much of the border is open hard-packed desert. Therefore creating new routes across the border is mostly as simple as visually marking out routes.

Once across the border there are brigade and divisional wide lanes leading:

From Basra to the petroleum ports near Bandar and then along the coast;

From Amarah and Basra to the major city and transportation hub of Ahvaz and beyond to the foot of the mountains; and

From north of Amarah to Andimeshk, which is the final transportation junction city before the foot of the mountains.

An advance down these lanes would involve an advance from the LOD to the end of the lane, known as the Limit of Exploitation (LOE) of 100-200 km. Like the 1980 Iraqi invasion, intermediate objectives would be Ahvaz and Bandar. After taking these objectives and the LOE America will have seized most of Iran’s oil fields, pipelines and petroleum ports.

The road network is dense enough to support an invasion force of 12-18 combat brigades. On this road network an American invasion force could logistically support an advance of 100-200 km without requiring pauses to consolidate.

The rate of advance would depend on Iranian resistance. This is the terrain where US forces have every advantage, so there is a good chance the advance up to the LOE would take only a few days.

However, this occurring is likely already part of Iran’s defensive plan. After the LOE American forces would be caught in the same kind of company wide advances along mountain roads as for the Turkish invasion routes.

Invasion Route - North

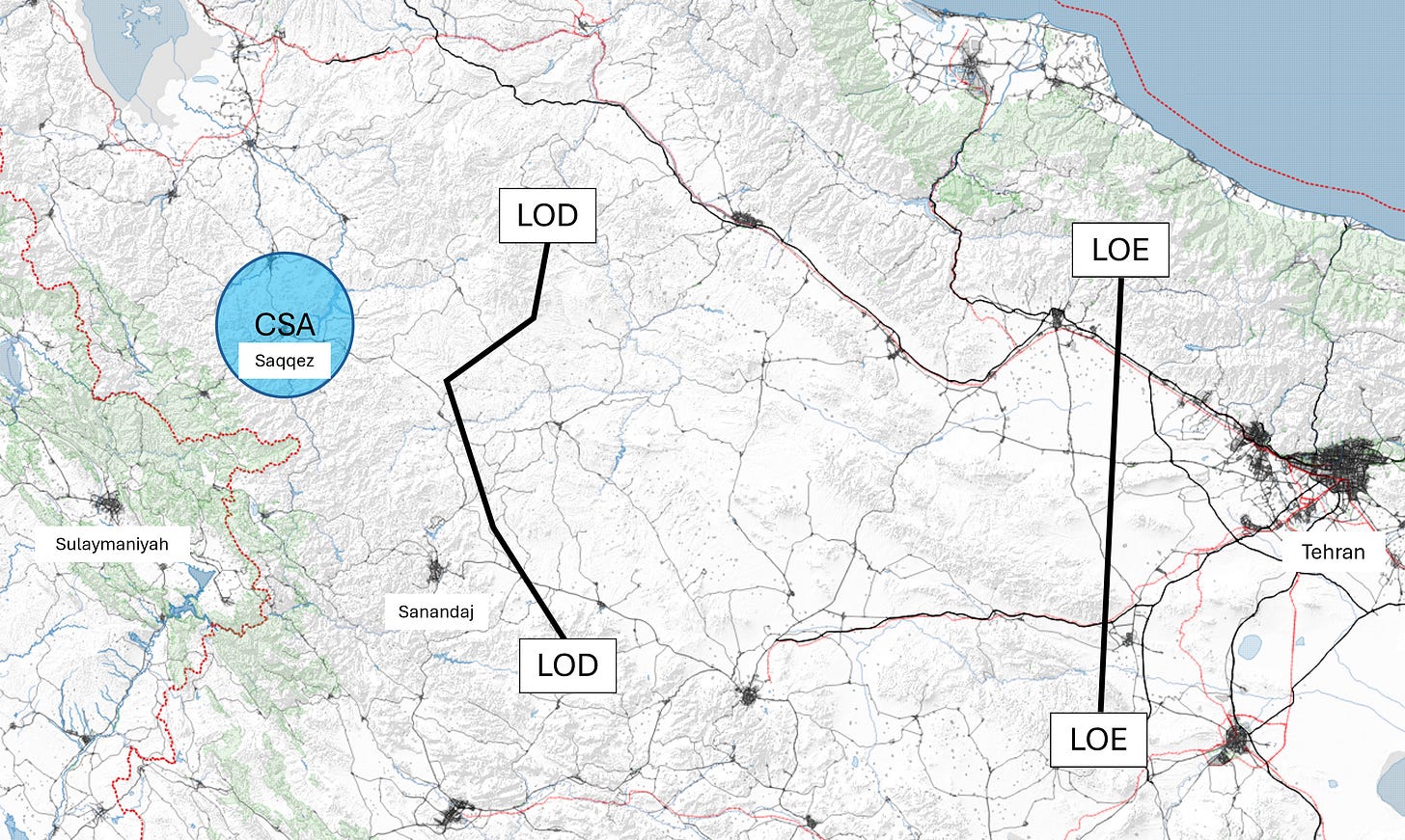

As we see from history, economics and terrain analysis, the obvious invasion route is in the south. However, there is a viable high-risk high-reward invasion route in on the northern part of the Iran-Iraq border near the city of Sulaymaniyah, with initial objectives of the Iranian cities of Baneh and Marivan, followed by Saqqez and Sanadaj as intermediate objectives.

This route is risky because it is the same mountainous terrain as the Turkish invasion routes to the north. The roads are still company wide corridors, but there are about three times as many roads per sq km because the population density is higher. This makes advances through the mountains between towns and cities a difficult but viable task.

The increased population is a double edged sword. The junction towns on the Turkish invasion routes like Jolfa and Bazargan had populations of about 10,000. Sanadaj has a population of 412,000, which is nearly twice the size of Falujah. The other three named cities in the map above have populations of 110,000 to 165,000. Sanadaj has some limited bypass roads, but the other three cities do not. This means if the Iranians stand and fight in the junction cities US forces will need to fight block by block through at least part of the city before resuming the advance.

In the map above I have drawn a LOE that is 100-250 km from the LOD. Given the slower rate of advance, likelihood of some urban combat and less extensive road network this advance would require at least one pause to reconsolidate. The lack of open terrain also means this invasion route could support 1 or at most 2 divisions.

The northern invasion route is high reward because after the LOE has been secured US forces can advance on Tehran in follow up operations. The area between the LOE and Tehran is a mixture of mountains and rolling hills. Since the terrain is less mountainous most of the towns and cities have bypass routes, avoiding the necessity of urban fighting. The spines of the mountains mostly run parallel to the axis of advance, making them less useful defensively.

This advance from the LOE to Tehran is 200 km deep and 120 km wide, making it a Corps level operation, which is twice the size of the force required to seize the LOE. Consequently there would need to be a significant pause (likely 5-10 days) between seizing the LOE and resuming the advance. Supplying this advance would be difficult. The rear area for this follow on operation has good highways, but they wind through the mountains and there is no connecting railway line.

Seizing Tehran would require another consolidation pause, another move of the CSA and then a third operation. On the positive side there are bypass routes around Tehran that make it possible to surround Tehran without fighting through it. This is a minor comfort in comparison to the enormous task of seizing Tehran. As of 2018 the greater Tehran area had a population of 16.8 million and an urban area of 1,704 sq km. This population is comparable to the greater New York area, and the urban area is approximately the same as the greater London area.

To put the size of Tehran in the context of recent conflicts, it is:

3x the size and population of Baghdad;

67x the population and 71x the size of Fallujah; and

233x the population and 41x the size of Bahkmut.

However, the northern invasion route is the closest thing to a gap in the ring of mountains that make up Iran’s national redoubt. Mounting an invasion along this route would be difficult and risky, but it could just possibly result in reaching the outskirts of Tehran within a month.

Example Manoeuvre Plan

The northern invasion route is too risky for me to stomach, as I suspect it would be for American planners. Below I have mapped out an example manoeuvre plan for the first sequence of operations for an invasion over the Iraqi border.

In the north 1-2 light infantry divisions (3-6 combat brigades) will advance towards Saqqez and Sanadaj. They will primarily act as a fixing force, to prevent too many units being sent south through a threat to the capital of Tehran. If this advance is unexpectedly successful the American commander could consider reinforcing this success and making it the main effort.

The main effort would be in the south, where a mechanised force of over four divisions (14 or more combat brigades) would seize Andimeshk, Ahvaz and Bandar, when advance up to the foothills of the mountains.

Including a reserve, flank guards and a substantial rear area security element this manoeuvre plan would require at least 25 combat brigades. So if America invaded Iran via Iraq it would have only a handful of combat brigades for operations on other invasion routes.

If this plan succeeded it would deprive Iran of most of its petroleum industry and provide initial victories for the Americans on terrain best suited to their military capabilities. However, this first operational sequence only sets up the national redoubt stage of Iran’s defensive plan.

Follow on operations would be needed to advance through the mountains and bring an end to the war. These subsequent operations would be considerably more difficult than advancing across the good tank country found near Ahvaz.

Conclusion

Unlike the invasion routes out of Turkey and Armenia, the terrain and transportation infrastructure make an invasion of Iran from the Iraqi border difficult, but viable.

Getting supplies into the CSAs would be difficult. Supplies would be shipped through the Persian Gulf, offloaded in Saudi ports, trucked by local contractors to Kuwait and southern Iraq and finally brought by rail to Erbil. All this would occur within range of Iranian missile and drone strikes.

In the north there is a high-risk high-reward operation that could allow an advance on Tehran. More likely the opening operation would see the seizure of the open terrain in south-west Iran around Ahvaz.

However, this would not be decisive. It would only set the stage for the national redoubt defensive strategy discussed in the first two parts of this series. This initial set of operations would only be decisive if the Iranian will to fight collapses after these early reverses, or if the air defence, cruise missiles and drone technology Iran relies upon is ineffective. Relying on the logic of “we have but to kick in the door and the whole rotten structure will come crashing down” is not sound military planning.

Therefore we will need to look at amphibious invasion via the Persian Gulf in the next part in search of a quick decisive blow against Iran.

Today 180-190 km is the ideal distance, which reflects American doctrine adapting from Cold War operations in Western Europe to the longer logistic lines of the War on Terror.

US AG, Operation Desert Storm: Transportation and Distribution of Equipment and Supplies in Southwest Asia December 1991 GAO/NSIAD-92-20 https://www.gao.gov/assets/nsiad-92-20.pdf.

![Iranian soldiers in close combat with Iraqi troops near Khorramshahr during the Iran-Iraq War [1000x577] : r/MilitaryPorn Iranian soldiers in close combat with Iraqi troops near Khorramshahr during the Iran-Iraq War [1000x577] : r/MilitaryPorn](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!UkM6!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F9b3cac5a-416b-4f51-807c-ffc2b77e5a7c_1000x577.jpeg)

Staggering to read this in light of events over the past week. Agree there is little appetite for ground operations, but Iran will definitely remain in the cross hairs for the foreseeable future. Count on a model of destabilisation similar to Syria, fomenting insurgencies among ethnic minorities and resistance groups. Undermining trade and diplomatic relations with neighbouring countries, attempts to strangle the economy and create a brain drain of their best and brightest seeking opportunities elsewhere.

I think we have avoided the worst consequences of an irrational and reckless war for now, thankfully.

But I fear more betrayal and instability in the region.

Excellent article. I doubt there is any interest in the administration for such a ground offensive. At most, perhaps the seizure of an island next to the Strait of Hormuz would be useful to protect shipping. But even that seems like too much.