Let's Invade Iran Part 7

Wargaming the Naval Battle

In the last episode we looked at the characteristics and capabilities of the USN versus the Iranian navy in the context of combat in the Persian Gulf. To support an invasion of Iran via Iraq or the sea the USN needs to force its way through the Straits of Hormuz and then escort merchant vessels through the strait. Iran’s naval defences revolve around mining the Strait of Hormuz and then engaging US ships with swarms of drones and Anti-Ship Missiles (“ASM”). Although the USN is a historically dominant navy, it is not well designed for combat with Iran in the Persian Gulf. Also, we have almost no historical data on how well a modern naval task force can repel a drone and ASM swarm.

This part will postulate about naval combat in the Persian Gulf. If tasked with supporting an invasion of Iran via the Persian Gulf the USN would almost certainly prevail, but at a significant cost up to the loss of light carrier task force.

Likely Naval Campaign Plan

Forcing the Strait - The Route

Even if the USN has a significant fleet in the Persian Gulf prior to hostilities, at some point a large group of US warships will need to force it’s way through the Straits of Hormuz.

Iran would respond with swarms of drones and ASMs. As mentioned in the previous post, there has never been a drone and ASM swarm attack on a naval task force with a modern missile defence system. On paper the missile defence systems can defeat a very large number of incoming drones and ASMs. However, these same systems were present on US and Israeli frigates that were struck by less capable ASMs that were launched as a single missile rather than in a swarm.

The mine threat is also significant, given the USN has been caught in a delayed transition between it’s 1980s era mine sweepers and the mine countermeasures mission module coming online for the LCS vessels.

Iran would also use it’s fleet of diesel submarines to support minelaying and the ASM/drone swarm attacks. These submarines are silent to the point of nearly undetectable when operating for short ranges on battery power. After hostilities begin surface minelaying would likely be impossible, but all of Iran’s submarines have extensive (for their size) minelaying capabilities. The submarines would re-plant minefields after US mine sweepers cleared an area, so that every ship transiting the straits would need to have the channel re-cleared.

All of Iran’s submarines can also launch ASMs from underwater out of their torpedo tubes. The Iranian submarine force would coordinate to launch their ASMs to be part of the ASM/drone swarm from surface and land based launchers.

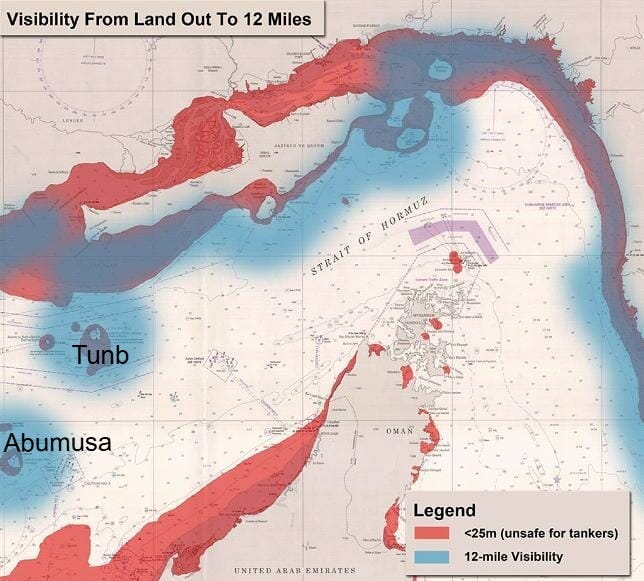

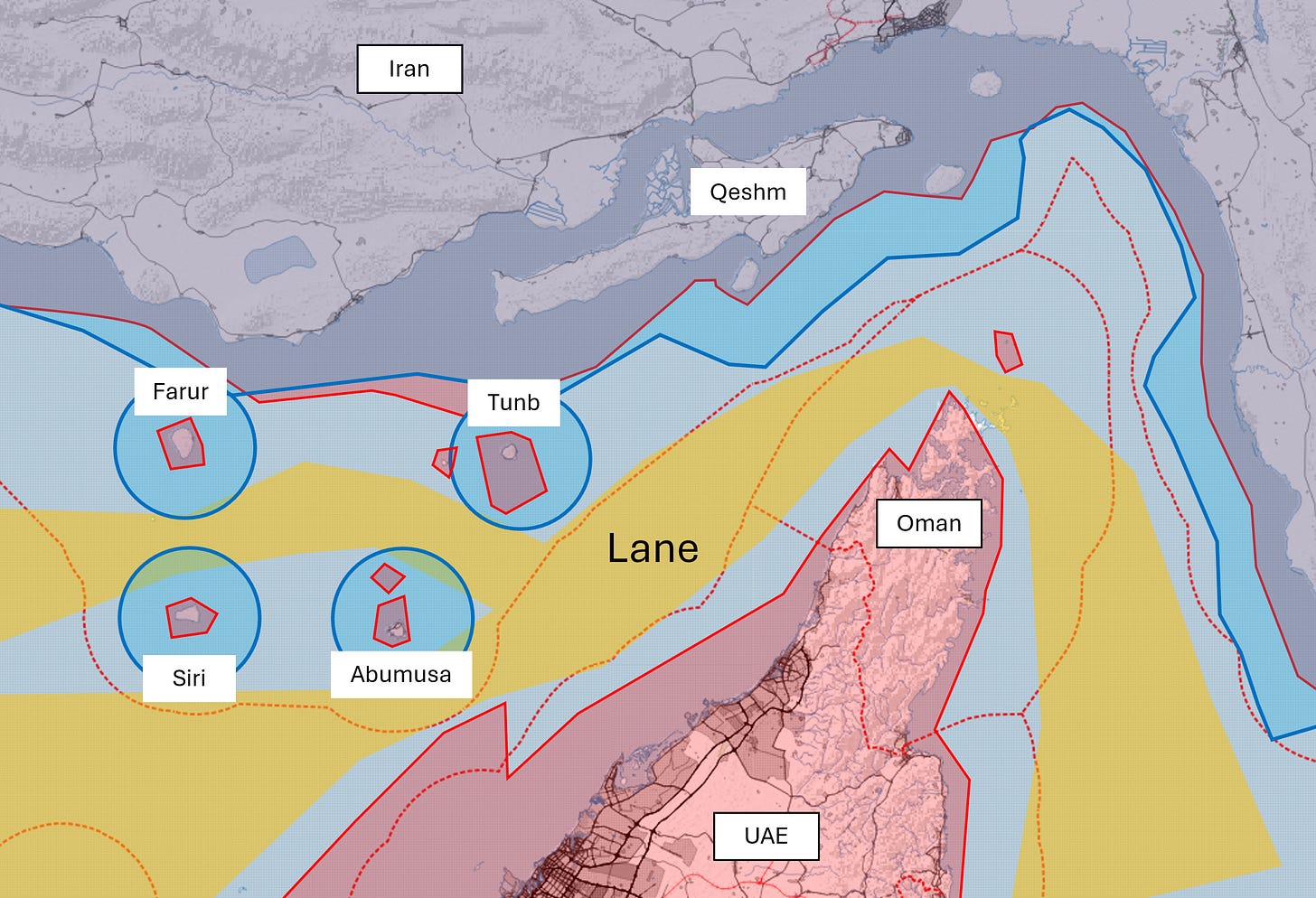

Forcing the Straits of Hormuz involves sailing an L shaped route 50 km wide and 200 km long. However, Iran owns several islands in the strait that the task force would want to avoid. There are two Iranian Islands (Abumusa and Greater Tunb) on the western side of the strait. These islands have the effect of extending the canalizing portion of the straits another 100km.

The USN would also avoid the shallower waters, not so much to avoid running aground as that mines are more effective in shallower water. This leaves a usable lane about 20 km wide and 300 km long the USN task force would use to force its way through the Straits of Hormuz.

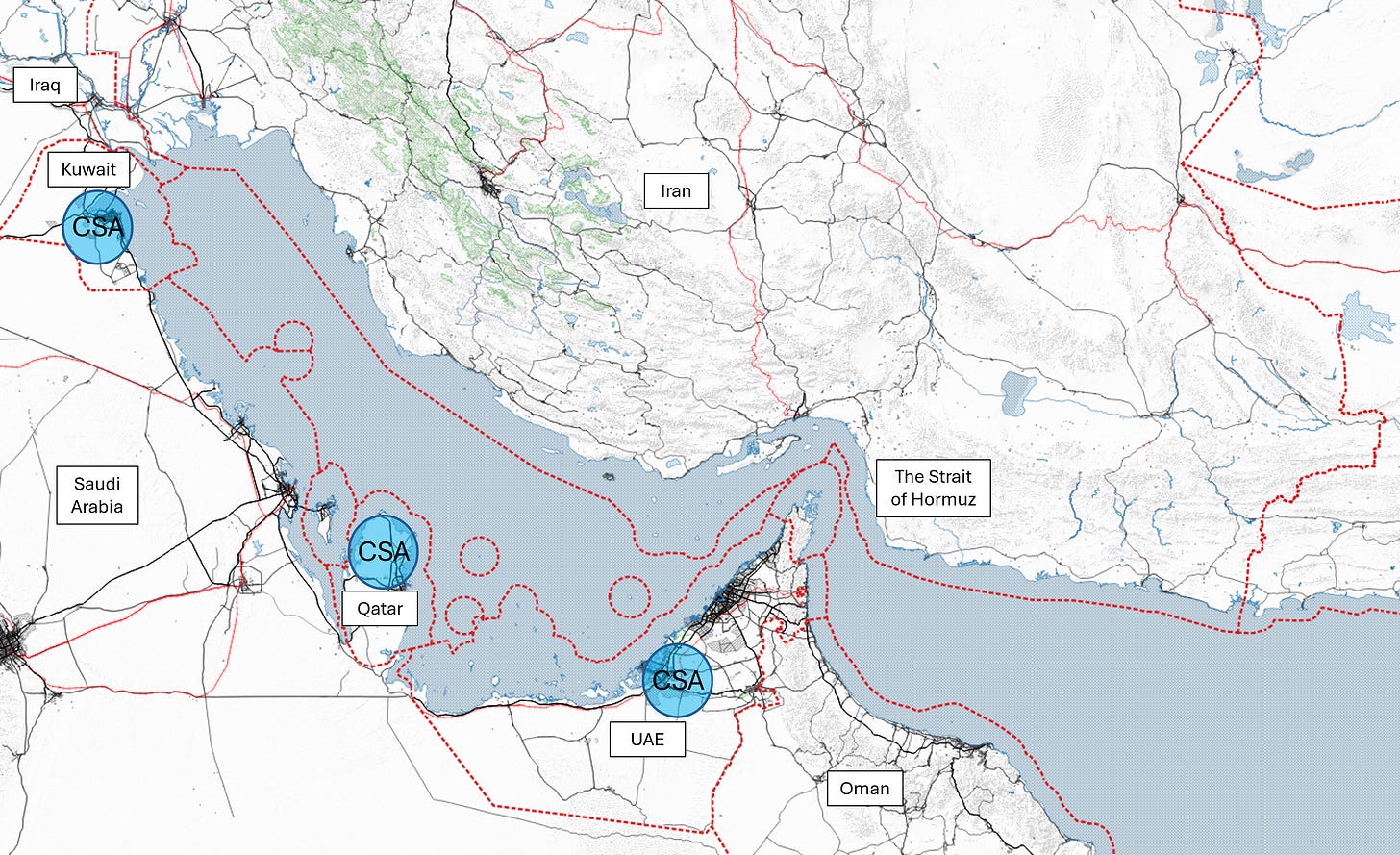

The map below shows the usable lane for a USN forcing of the Straits of Hormuz:

The usable lane is in orange;

The blue shaded area is in visual range of Iranian controlled territory. These areas should be avoided, but can be navigated at increased risk; and

The red shaded area is land or waters that are too shallow for the larger warships in the task force. They can be entered by the escort vessels.

A task force must travel at the speed of it’s slowest vessel. So with the Avenger class minesweepers making up to 15 knots it would take at least 12 hours to transit the strait. If enough mine-sweeping LCS’s are available the task force could make over 20 knots for a transit time of at least 8 hours. This is more than enough time for Iran to mount multiple coordinated drone and missile swarm attacks.

The lane itself also favours Iran. It narrows to about 8 kilometres at the northern tip of Oman. It narrows to about 15 kilometres when passing by the four Iranian held islands. The task force will also need to come within visual range of these four islands.

This naval canalising terrain is dangerous for several reasons:

Visual spotting does not give off an electronic signature like longer range systems like radar. The USN relies heavily on these electronic signatures for suppressing shore based naval defences;

Canalised terrain gives ships little ability to manoeuvre. Manoeuvring is one form of defence against ASMs, torpedoes and suicide fast boats;

Iran can concentrate assets in the canalised terrain, knowing the task force needs to pass through that narrow area; and

Most importantly, mines are most effective when concentrated in canalising terrain.1

Forcing the Strait - the Task Force

Notwithstanding my many caveats of this not being my area and the paucity of historical data, the USN is clearly capable of forcing through the Straits of Hormuz. However, they would probably lose several ships in the process.

Transit through the straits would be proceeded by an air campaign to suppress Iranian shore based ASM launchers, the Iranian air force, command & control and the Iranian navy. The task force would probably include super carriers. Given the operational range of USN aircraft like the Super-Hornet their super carriers could provide air support from outside the straits in the Gulf of Oman. However, the reduced range, reduced payload and added reaction time would limit the carrier air group to defending the fleet in the Persian Gulf and limited airstrikes on Iranian positions close to the shore. Although risky, the USN would probably transit super carriers through the Straits of Hormuz, as this would greatly increase the air groups contribution to the offensive air campaign.

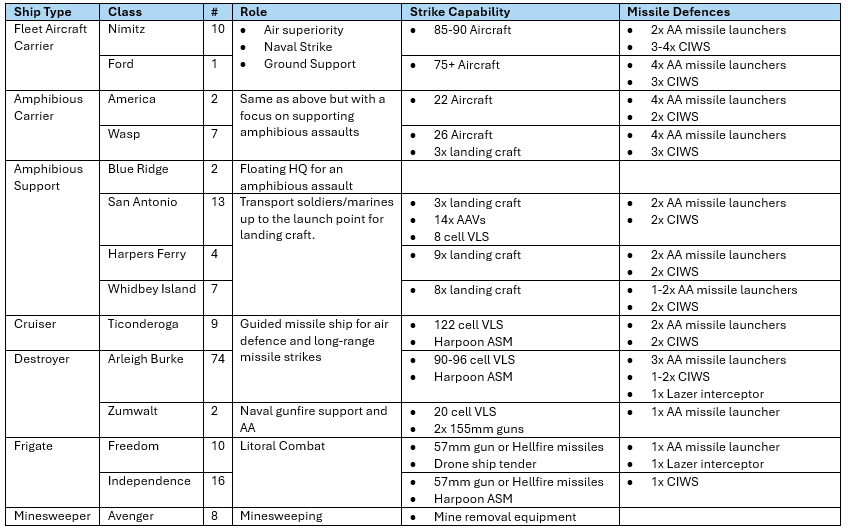

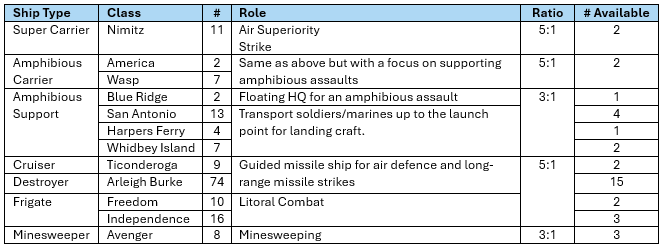

The table below shows the portions of USN’s surface warship fleet that could be used in the Straits of Hormuz, along with their key capabilities:

However, these numbers need to be reduced significantly to understand what would be available for operations in the Persian Gulf. As a rule of thumb you need five vessels for every one vessel on station in an operational theater.2

The 5:1 ratio only applies to the types of vessels that are usually kept on station, such as carriers, escorts and fleet sustainment ships. Amphibious support ships and other specialized vessels can use a 3:1 ratio. Therefore the following ships would potentially be available for a forcing of the Straits of Hormuz:

If I were designing the task force (a terrifying thought for any sailor) I would include the following vessels:

An Escort group, consisting of:

3x Minesweepers (Avenger class until such time as the LCS mine countermeasures program escapes perpetual failure mode);

12-16x Arleigh Burke or Ticonderoga class as anti-air and anti-submarine escorts; and

2 -5x LCS as escorts against Iran’s small boats.

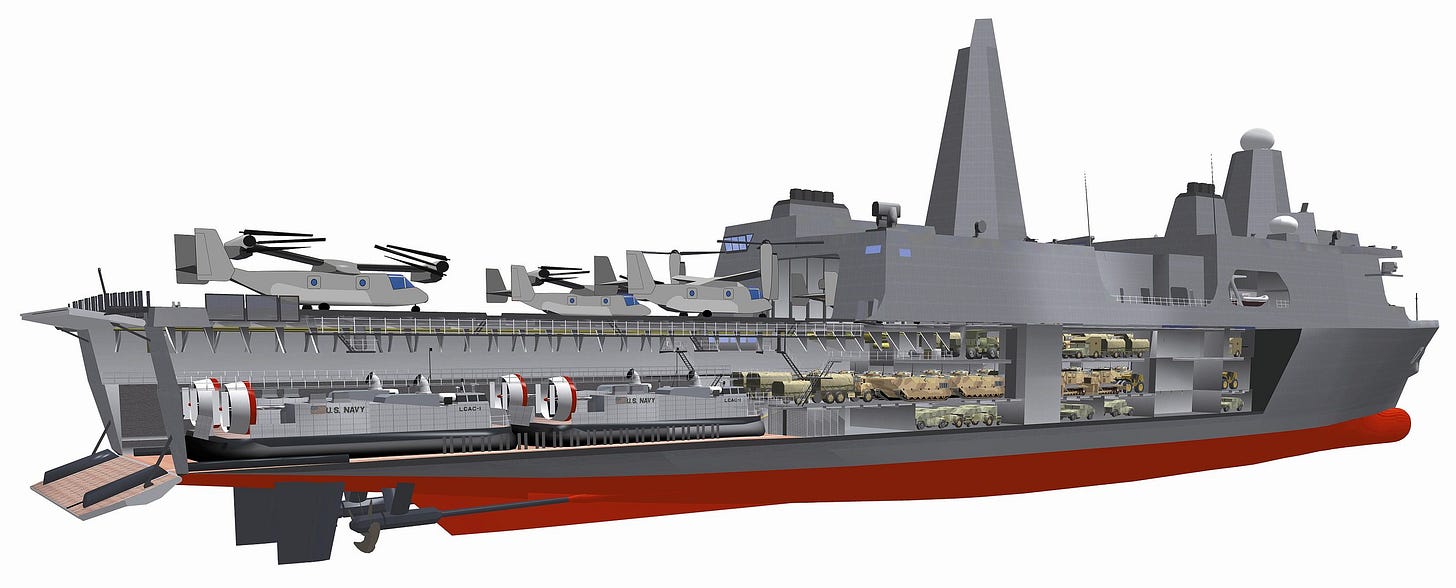

A Support group, consisting of:

2x Nimitz Class super carriers for establishing air superiority over the straits and supporting an air campaign inland;

2x America or Wasp class light carriers3 for local air support and amphibious support;

1x Blue Ridge class Amphibious Command Ship;

7x Amphibious support ships (Transport Dock or Dock Landing Ship) ships;

Various logistics support vessels.

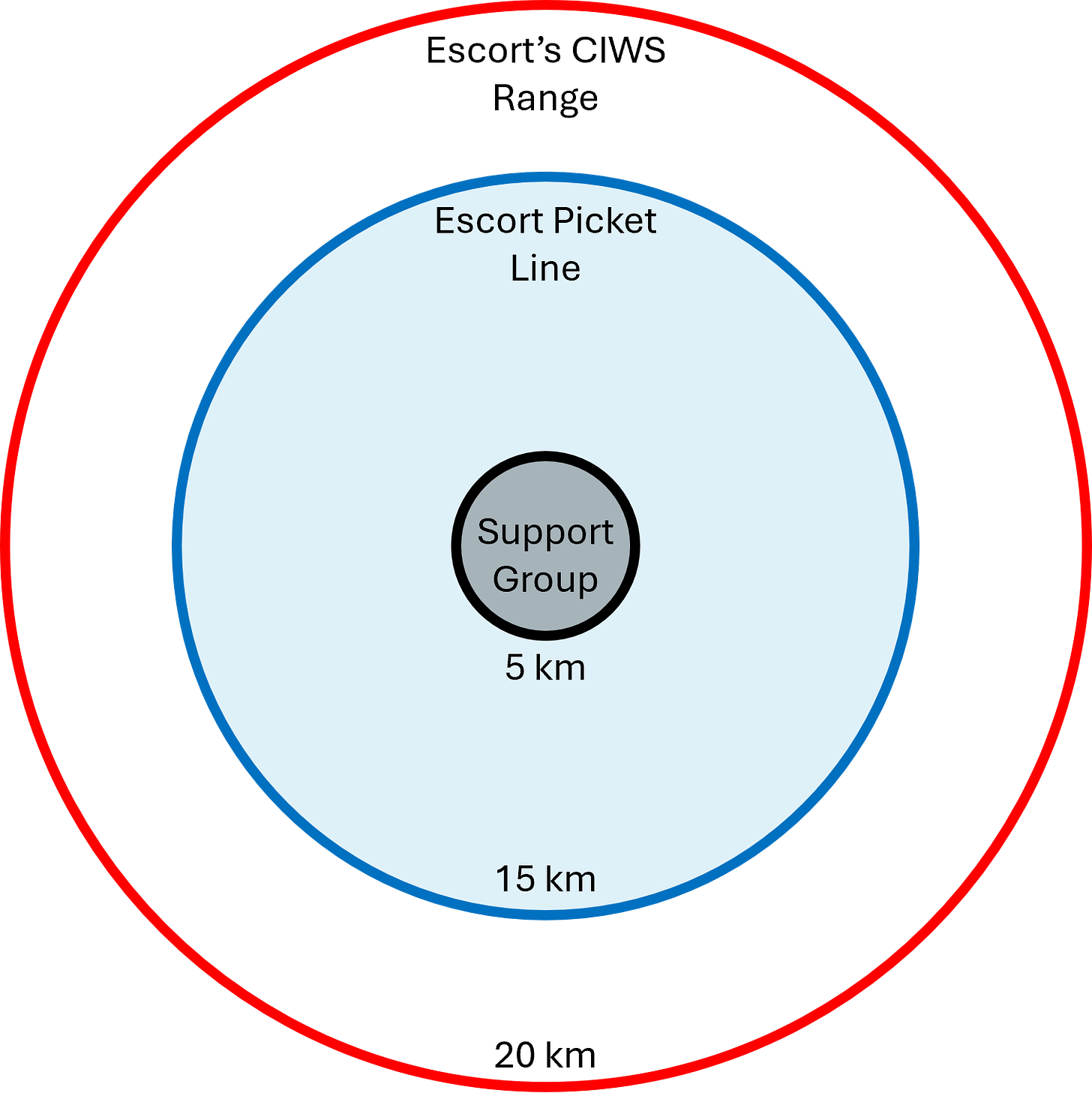

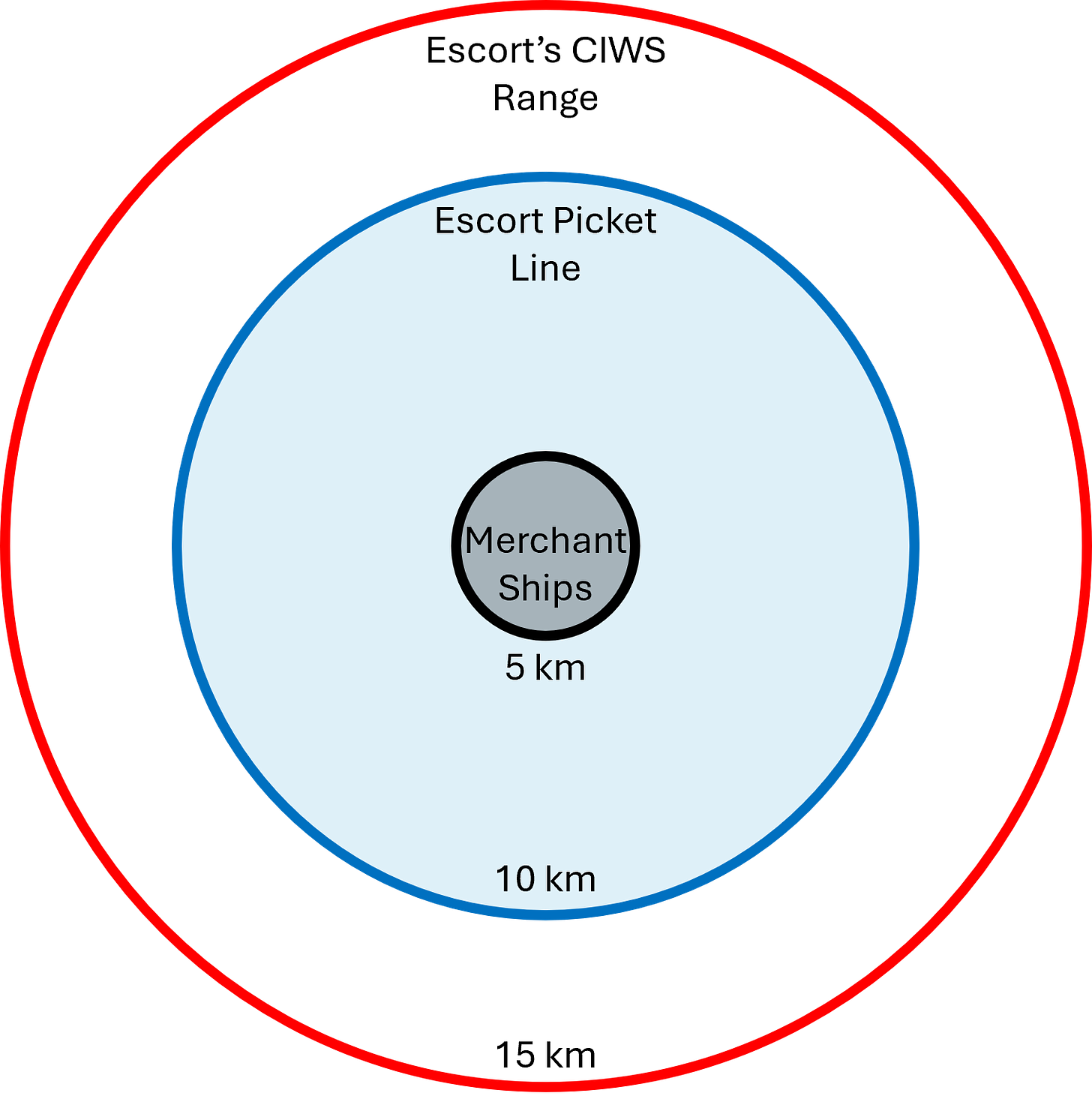

The Support Group would sail in a roughly circular convoy with a diameter of about 5 km. Most of the escorts would form a picket line with a diameter of up to 15 km. Various CWIS systems have an engagement range of approximately 5 km, so the entire task force would be able to engage ASMs and drones with CWIS across a circular area with a 20 km diameter.

At this spacing the escorts may not have overlapping CIWS coverage, depending on the exact location, the type of CIWS system and the number of escorts. The support group would be sailing in tight enough formation that at least half of their 30x CIWS systems could defend against an attack on any one ship. This means it would be much easier to overwhelm the escorts with a swarm attack, as you only need to overwhelm 2x CIWS systems rather than at least 15x when attacking the Support Group.4

The Escort picket diameter can be tightened up to allow overlapping CIWS coverage. However, this undermines the role of the Escort picket, which it to detect and engage targets at the maximum possible range.

Looking at the historical data and having spoken to a few knowledgeable people, I would divide the outcome of a forcing of the Straits of Hormuz into the best case, most likely and worst case scenarios.

Best Case Scenario

As a best case scenario the various missile and drone defence systems would work approximately as predicted in pre-war testing and exercises. The preparatory air campaign would be broadly successful in destroying the majority of Iranian ASM, drone, coastal submarine and small boat assets before they were dispersed. Iran also is unable to lay a significant minefield in the straits prior to the preparatory air campaign.

A large number of ASMs and drones would still be launched, but in an uncoordinated manner. A few would probably impact USN warships, causing casualties and vessels limping back to nearby friendly harbours. However, USN warships should be able to absorb a single Iranian ASM or drone hit without sinking.

Most Likely Scenario

The most likely scenario is that the defence systems are not as effective as expected, and Iran’s naval defences are only partially suppressed. A significant minefield is laid prior to the preparatory air campaign. There are a few mine strikes on USN ships, but the main impact is to slow down the task force, increasing the time in the canalizing high danger area. This delay allows Iran to regroup and reorganize, launching fairly well coordinated drone and ASM swarm attacks simultaneous with small boats.

Given all these factors the USN would likely lose several warships after taking several hits from ASMs, drones or small ship attacks. However, losses would be confined to the outer escorts, with the super carriers, light carriers, amphibious group and support ships avoiding significant damage.

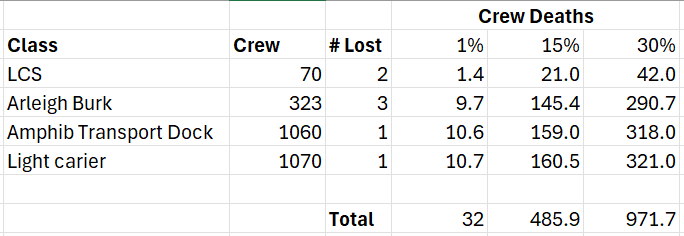

Under this scenario the USN could expect to lose 2-3 Arleigh Burke class destroyers and/or LSC’s. This would be the greatest loss of warships by any navy since the second world war.5 Under this scenario the USN would suffer several hundred casualties within a 12 hour period.

Worst Case Scenario

The worst case scenario involves the missile defence systems functioning very poorly, the Straits of Hormuz being fully mined prior to hostilities and Iran successfully dispersing assets to make the preparatory air campaign of marginal effectiveness.

Under this worst case scenario the USN is likely to lose 3-5 escorts and 1-2 of the larger vessels, like the light carriers or amphibious transport docks. Historically when a warship is sunk the crew suffers a 1-30% fatality rate. Applying this range to the ships involved to the worst case scenario could have almost a thousand American fatalities.

However, this is very much extrapolating the worst casualty figures from the worst case scenario. According to Raging Mandril, who you should follow, the Iranians are much more likely to focus their resources on easier targets, like the supply convoys that would need to transit the straits periodically throughout the remainder of the war.

Even in this worst case scenario I have not included the loss of a super carrier. They have more than three times the anti-air defence capabilities of the light carriers, so even if the ASM defence systems function well below expectations Iran is unlikely to have more than one or two missiles or drone strikes on them. Their sheer size makes them much more resistant to damage. The mines would be the biggest threat to the super carriers, but it would take quite a few mine strikes to sink a super carrier.

Supply Convoys

To keep an invasion via Iraq or the Persian Gulf supplied requires a flow of merchant shipping to pass through the Straits of Hormuz. Initially these would be to supply the Corps Service Areas (CSAs) that would be located near one of the ports in Kuwait, Qatar and/or the UAE.

This means perhaps once a week or more sailing a convoy of merchant ships through the Straits of Hormuz, to the CSA port and then back out the strait. An escort group of perhaps a dozen, consisting of Ticonderoga cruisers, Arleigh-Burke destroyers, LCS’s and minesweepers would be required for each convoy. This smaller escort group means the radius of the picket line and CWIS range would contract.

For the task force breaking into the Persian Gulf in the center is the Support Group, with the of light carriers and amphibious ships. Most of these ships have 2x CIWS systems, so the center of the break in task force also has the highest density of anti-missile defences. For the supply convoys the center of the task force holds the merchant ships, which have no missile defence systems. So the task force breaking into the gulf is like an avocado, with a somewhat hard outer shell (the picket line) and a hard inner pit (the support group). Conversely, the supply convoys are like an egg, with a fairly hard outer shell protecting a soft, vulnerable center.

Raging Mandril’s comment that Iran would prefer to focus on the supply convoys made up of merchant ships makes good sense, to the point it might seem suicidal to even attempt to run these merchant convoys through the Strait of Hormuz. However, there are two mitigating factors:

Moving the task force through the straits, and follow up operations against Iran would significantly degrade Iran’s ability to mount coordinated follow on attacks on the later supply convoys; and

Iranian drones and ASMs have proven good at damaging merchant vessels, but have a poor track record for sinking them.

The operation to push the task force through the Straits of Hormuz would be preceded by an air campaign, and during the battle to sail through the straits the US military would do serious damage to Iran’s Command & Control, navy, air force, radars, ground based ASM launchers and air defences. The amphibious group would then conduct landings that further reduced Iran’s ability to contest the strait, but that is the topic of the next post.

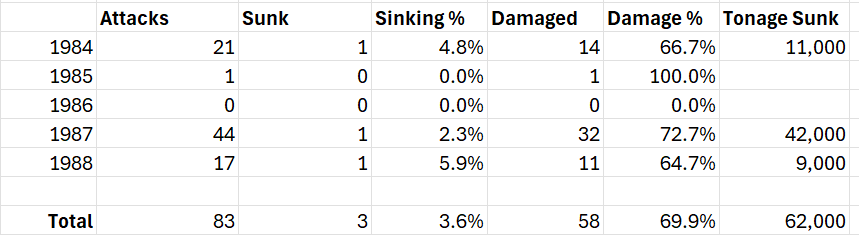

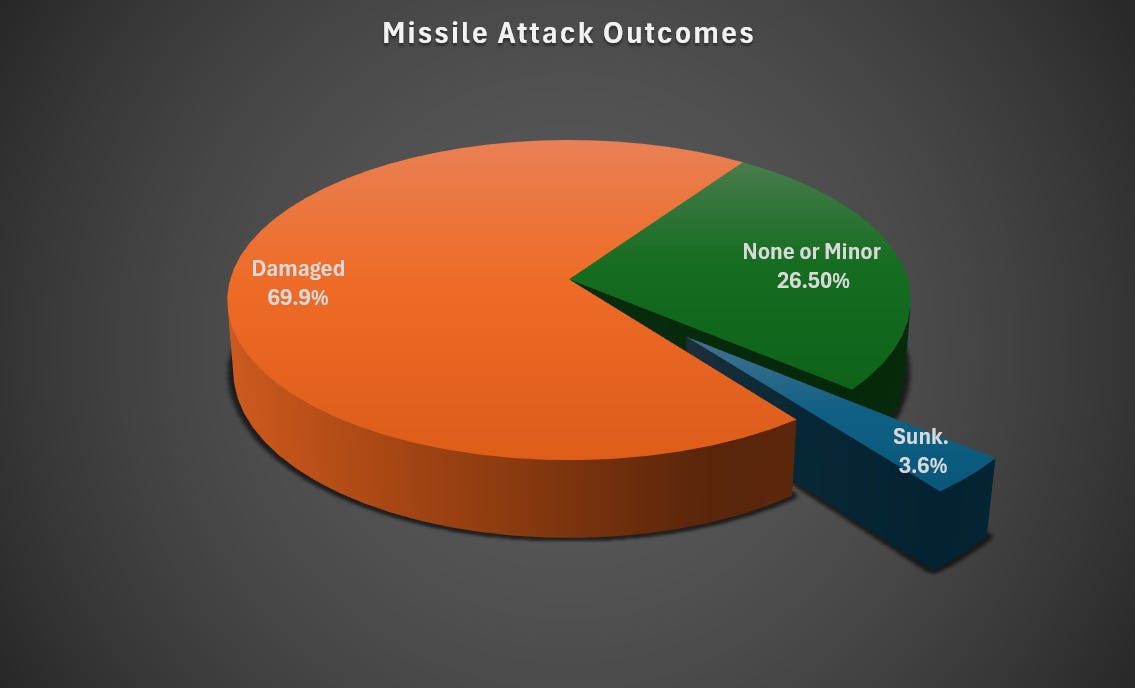

It is also surprising how ineffective the types of drones, small boats and ASMs Iran employs have been at sinking merchant vessels. During the tanker war during the Iraq-Iran War dozens of oil tankers were hit by ASMs and small boats (drones weren’t yet a factor). From the chart below, we see there were 83 missile or small boat attacks on shipping in the Persian Gulf from 1984-88.

Only 3.6% of these attacks successfully sunk a merchant vessel. Of these three sunk merchant vessels only one, an oil tanker called the Norman Atlantic, was a large ship at 42,000 tons. She was sunk by Iranian Revolutionary Guard members in small motorboats.

However, the missile and small boat attacks were very effective at damaging merchant ships, with a success rate of 69.9%. The given merchant ships are crewed by civilians, operated by corporations and need obtain insurance for each voyage, creating a significant rick of damaging the ship is often enough to shut down a shipping route.

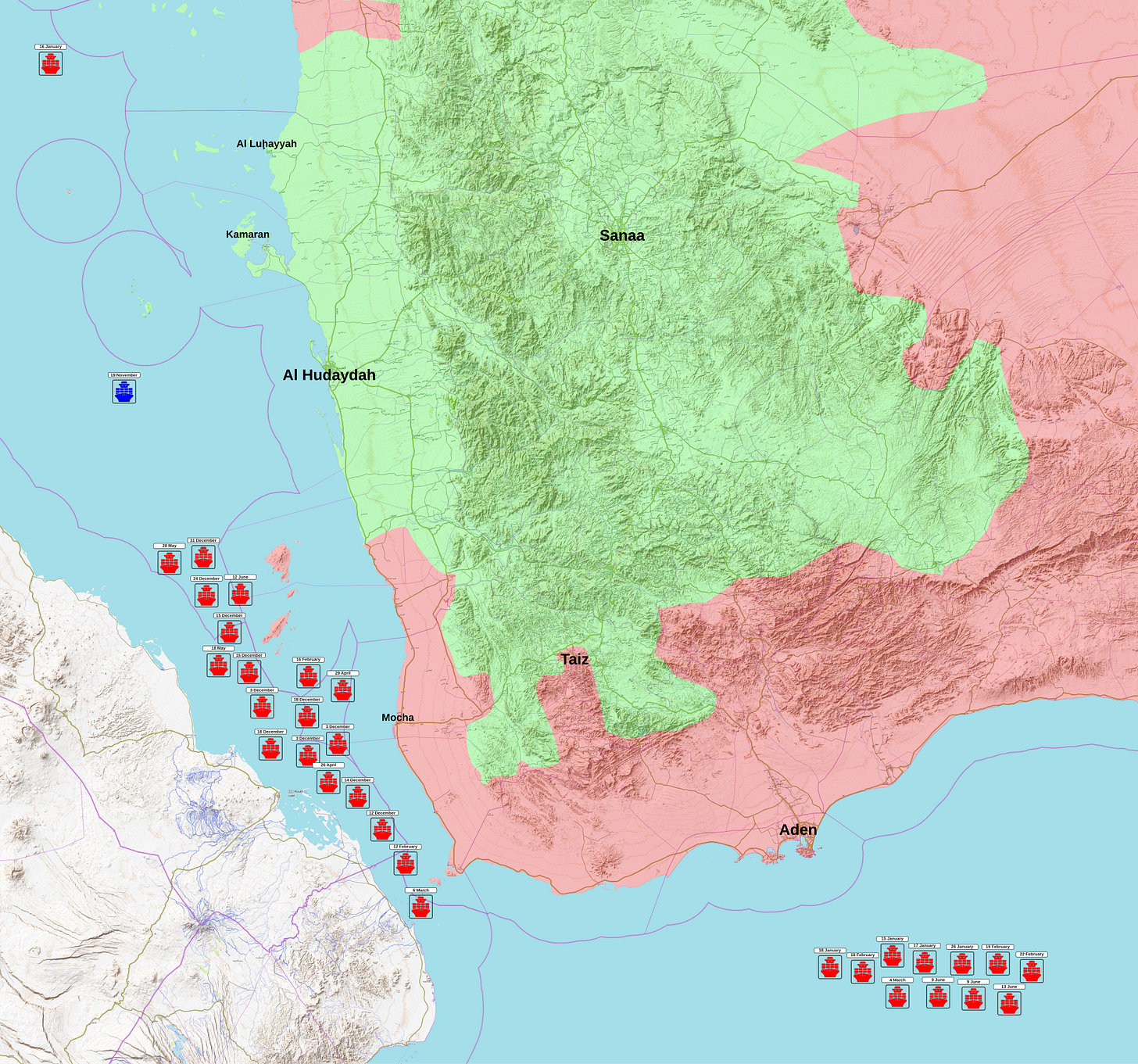

Another applicable historical is the Houthi Red Sea campaign of 2023 to present. The Houthi rebels used a combination of Iranian drones, Iranian ASMs and motor-boats with insurgents to attack shipping in the Red Sea on it’s way to the Suez Canal.

Over the last two years they have damaged 31 merchant ships and significantly reduced traffic through the Suez Canal. They accomplished this mostly using Iranian supplied equipment. They have only used medium range ASMs and drones, as the damages vessels were all 80-200 km from Houthi controlled areas.

However, so far the Houthis have only sunk two ships, and both sinkings suggest Iran’s ASM and drone swarms might not be very effective against merchant vessels. On February 18, 2024 the Houthis launched two Iranian supplied ASMs at the MV Rubymar. One of them struck, causing significant damage. The crew abandoned ship, but the the Rubymar did not sink. The Rubymar finally sank after two weeks of floating adrift and unmanned.

On July 7, 2025 the Eternity C was struck by a single Iranian supplied drone, causing some damage. The Houthis followed up the drone attack with several RPGs fired from motor-boats. The next day the Houthis fired six ASMs, 2-3 of which struck the vessel. Although the Houthis claimed these ASMs sunk the vessel, it appears it only caused the crew to abandon ship, after which the Houthis boarded and sunk her with demolition charges.

Looking at the Houthi campaign and the Tanker War, modern merchant vessels have proven remarkably resilient to ASM and drone strikes. Size alone makes most modern merchant vessels a difficult target. Most modern merchant vessels are much larger than any warship except carriers. For example, the MV Rubymar is a small merchant vessel, but it is over twice the tonnage of an Arleigh Burk destroyer and half the tonnage of a light carrier.

Modern warships have active defences (like AA missiles and CIWS), but if an ASM strikes they are usually a more vulnerable target than a merchant vessel. Modern warships have almost no armour, but they do carry a large amount of explosives in various magazines.

The USN can certainly escort merchant ships through the Persian Gulf, and intercept enough ASMs, drones and small boats to ensure very few merchant ships sink. However, a large number of these merchant ships would be damaged in the process, which would make the commercial shipping companies refuse to cooperate.

There are ways to overcome the objections of the commercial shipping companies, but they are fiscally and politically expensive. The US Department of Transportation maintains a small fleet of merchant ships as the National Defense Reserve Fleet that can be used to support military operations in areas too dangerous for commercial shipping companies.

However, the NDRF is too small for America’s current overseas commitments and the vessels themselves are in very poor condition. In 2019 they conducted a practice mobilization there only 40% of ships could be activated and crewed in the timeframe established by congress. Since then there have been attempts to reinvigorate the NDRF, but those efforts have mostly highlighted the incompetence of the US Department of Transportation.

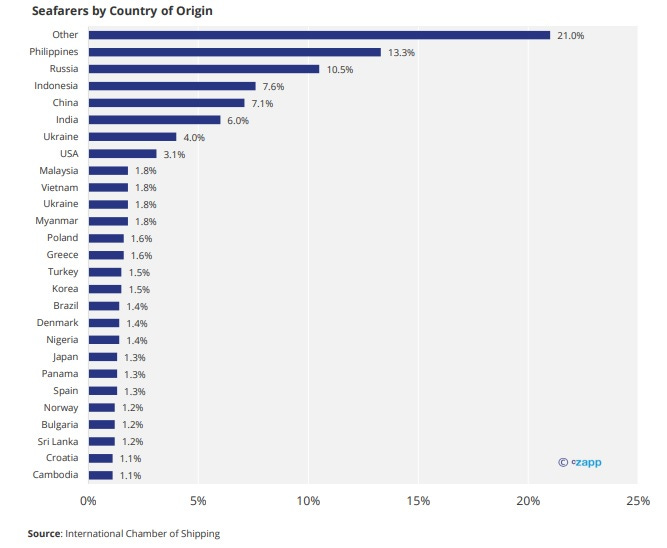

If the NDRF were rebuilt, or if the US government purchased enough merchant ships to run it’s own convoys into the Persian Gulf they would face severe issues crewing the vessels. US Seafarers are capable of being pressed into service, but US Seafarers are hard to find these days, with most commercial ship crews coming from the Philippines, Russia, Indonesia, China and India.

My general assessment is that running supply convoys through the Straits of Hormuz would result in a lot of damaged ships, but not many sunk vessels. The US would need to spend a lot of fiscal and political capital to assure enough ships and crews are willing to operate this dangerous shipping route. It appears to be viable, but there would be tremendous pressure on the US military to improve the situation through the amphibious landings I will discuss in the next part.

Approaching the Shore

To conduct these amphibious landings the amphibious task force would need to approach Iran’s coastline, both for the initial assault and regularly to bring supplies ashore. This would bring US ships into the range of Iran’s much more numerous short range ASMs and drones.

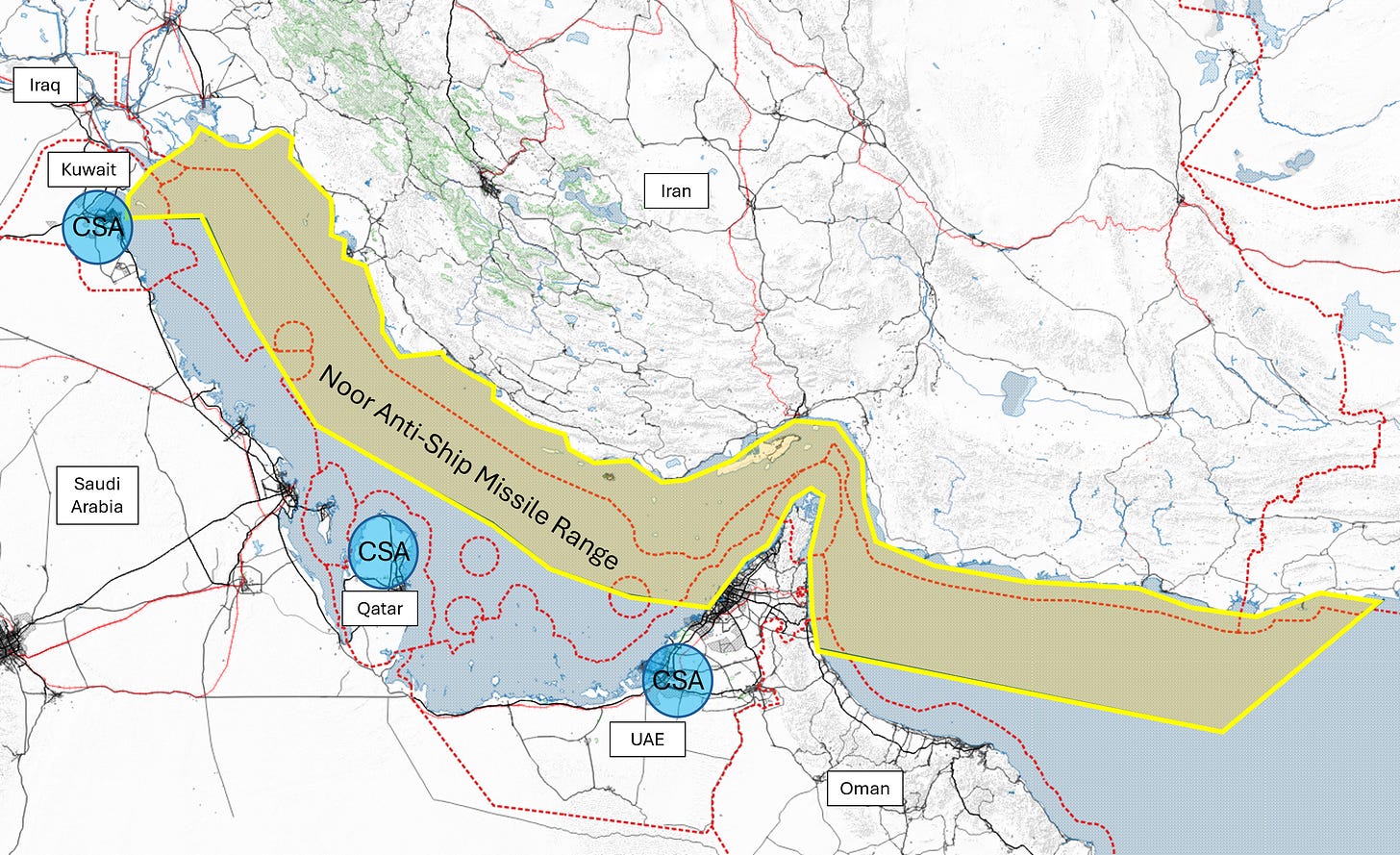

The most numerous of Iran’s short range ASM systems is called the Noor. In the map below I have shown the range of the Noor in yellow, as this is a good yardstick for where Iran can launch a swarm of cheap short range ASMs and drones.

Due to the need to mine sweep it would take several hours for the amphibious task force to cover the approximately 150 km from this danger zone to the disembarkation area. They would then need to remain in the danger zone for hours or days longer to logistically support the troops ashore. This would give plenty of time for Iran to launch a coordinated drone and ASM swarm attack.

The weapons, countermeasures and risks would look similar to the task force’s initial push through the Straits of Hormuz. The amphibious task force would be within range of Iran’s short range ASMs and drones for a longer period of time. However, Iran’s anti-ship capabilities would be further degraded after the battle of the Straits of Hormuz. Depending on how well the US had attrited Iran’s naval defence capability the USN could suffer similar losses to it’s forcing through the Straits of Hormuz.

Conclusion on the Naval Campaign

The USN is very much capable of transiting the Straits of Hormuz, escorting supply convoys through the strait and approaching the Iranian coast in support of amphibious landings. Despite being built for a very different type of war, the USN has more than enough ships and capabilities to accomplish these tasks.

However, these tasks would come at a cost. Even the best case scenario has the USN warships and transportation ships being sunk. Under the worst case scenario the USN would lose over half a dozen ships and have hundreds killed in action.

If called upon the USN would fight and win these battles in the Persian Gulf. One of the hallmarks of being a naval hegemon is the willingness to take losses in order to accomplish a necessary mission.

Throughout World War Two Axis naval strategy revolved around finding every possible way to not lose ships. After the loss of the Bismarck Hitler effectively had the Kriegsmarine’s surface fleet confined to home waters for the remainder of the war. By contrast, the Royal Navy lost 124 warships and submarines in the Mediterranean, but considered that campaign a success because the effectively supported land operations in the region.

During the darkest point of the war for Great Britain the Royal Navy was tasked with evacuating the army from Crete (another in a long line of humiliating evacuations). The Germans had air superiority and a new guided glide bomb. The Germans sank three cruisers and six destroyers, and damages two battleships, a fleet carrier and 19 other vessels. Due to these losses his staff urged him to call off the evacuation. His response typifies the attitude required to maintain hegemony as a naval power:

"It takes the navy three years to build a ship. It will take 300 years to build a new tradition. The evacuation will continue."

Admiral Andrew Cunningham

If called upon the USN would ensure an invasion of Iran could proceed via the Persian Gulf. Among other reasons, failure to do so would signal the end of the USN’s historically unprecedented naval dominance. However, the national leadership should only burden the USN with this mission under the clear understanding it could cost several ships and hundreds of sailors’ lives.

My apologies to to Raging Mandril, and any other navy readers for using landlubber terms (lane instead of passage, canalizing terrain instead of enclosed waters etc). Even when analyzing naval warfare I remain a soldier.

For very warship on station there is one in maintenance, one in refit, one in training and one in transit. Ships can be surged for a short term increase in numbers, but this has a delirious effect for a long time afterwards.

These classes are called Amphibious Assault Ships by the USN, as their primary role is supporting the USMC. They carry helicopters and Vertical Take of and Landing F-35s. By international standard terminology they are light carriers or jump carriers.

I am focusing on CIWS because it’s the last line of defence and easy to understand. There’s a more complex battle against the drone and ASM swarm involving medium to long range anti-air missiles that the falls on the Ticonderoga and Arleigh-Burke class in particular. However, almost everything I need to know to assess this medium to long range battle is classified and highly dependant on the specific engagement.

During the entire Falklands war the Argentine and Royal navies lost 1 and 2 warships respectively. Each side’s losses in tonnage total less than the combined tonnage of an Arleigh Burke and an LCS.

The biggest gap in this analysis is lack of air force or army participation. I would guess that seizing islands like Tunb and Abumusa would take place early in the war by airmobile units. Taking Qeshm would be logical too. Hengam Island is 40 miles from Oman, easily within reach of airmobile units. Take that, build a forward operating base, take Qeshm. Taking Larak and Hormoz Islands neutralizes the Iranian Navy at Bandar Abbas.

Britain lost 4 warships during the Falklands war. 1 RFA ship, 1 merchant ship and 1 landing craft. The loss of Atlantic conveyor nearly ended the war due to loss of helicopters.

Great article otherwise. I think the rule that fort beats ship still applies.