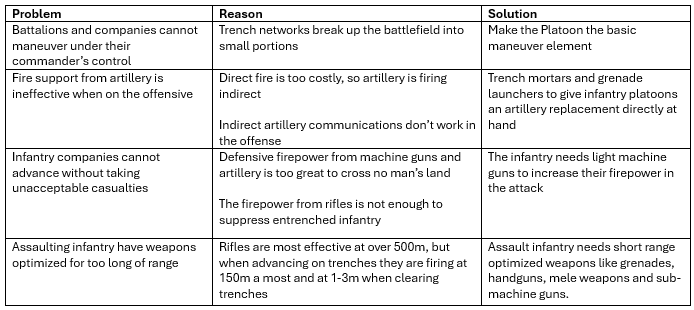

The last post discussed how World War One began with the infantry operating at the battalion level while almost uniformly armed with bolt-action large cartridge magazine rifles. By 1915 most armies identified the infantry needed to operate at the platoon level with a mix of trench mortars, grenades, light machine guns, mele weapons and sub-machine guns.

In this post we examine how the proposed solutions of 1915 translated into adopting new weapons in 1915-18. The weapons adopted were almost universally prewar designs that were hammered into new roles like a square peg into a round hole.

This collection of adapted infantry weapons were adopted in 1915 and produced on a mass scale by 1916. By summer to fall 1916 the major armies had platoons with a collection of crude weapons roughly equivalent to those used by modern infantry.

Picking A Cartridge

Of direct application to the initial question about 5.56 vs 7.62 mm ammunition: The redesign of infantry weapons in 1915 opened up a number of still unsolvable trade offs in the structure and equipping of an infantry platoon.

Prior to 1914 there were two relevant weapons in an infantry battalion, the full powered rifle and the heavy machine gun (HMG). Both needed the same characteristics for their cartridge. After 1914 the infantry platoon (an organization two layers smaller) ideally needed:

A HMG for firepower in the defense. To be effective it needed:

A full powered rifle cartridge to be effective at over 500 m;

Recoil was not an issue because it would be mounted on a tripod; and

Weight was not an issue because it would be static.

Light machine guns (LMG) for mobile firepower on the attack. To be effective it needed:

A mid-sized cartridge to be effective at 100-500 m;

The cartridge should be smaller to allow more to be carried while on the attack;

The recoil should be less than the HMG as it would fire from the hip and from a bi-pod.

Close range infantry weapons for assaulting positions and clearing trenches. To be effective they needed:

A firearm with a light pistol caliber cartridge for quickly putting out a lot of fire at 150 m and below;

Weapons for extreme close range when clearing trenches, such as a shotguns, grenades and short edged weapons like trench knives and machetes;

Because so many soldiers would now have non-rifleman tasks, a close range self-defense weapon. To be effective they needed:

Also a light cartridge effective at 150 m and below, but there was less of a need for a high volume of fire;

To be light, compact and easily slung out of the way so the soldier could easily service their main weapon (like a HMG or mortar);

An indirect fire weapon to provide instant fire support under the platoon’s direct control. To be effective it needed:

To be easily portable to stay 100-300 m behind the advancing infantry;

To have enough range to engage targets beyond the range of the rest of the infantry platoon’s weapons;

To be capable of rapidly firing for brief periods to approximate the effect of artillery; and

To not take too much manpower or supplies away from the platoon’s assault infantry.

Hopefully the problems are beginning to become clear. For example:

If each firearm were given the optimal cartridge the infantry platoon would carry a minimum of four types of ammunition. This creates a logistics nightmare and makes the platoon inflexible;

If every soldier should be proficient in all the platoon’s weapons, the infantry platoon would go from two weapons (the rifle and bayonet) to at least seven;

Standardizing the cartridge for any of the firearms requires compromising their effectiveness;

Combining any of the weapon categories (for example a combined HMG and LMG) leads to ‘jack of all trades master of none’ solutions; and

Every soldier operating machine guns or indirect fire weapons takes away from the assault infantry’s strength. The assault infantry rely on shock effect, which requires numbers. They also take the most casualties. Therefore the smaller the assault infantry component the less an infantry platoon can maintain offensive operations in the face of casualties.

The solutions they settled on in World War One were not ideal. They were a compromise made under wartime conditions. For choice of cartridge, every Army chose not to introduce a new cartridge mid-war. This meant every weapon had to be designed around either the full powered rifle cartridge or the pistol cartridge that was in use prewar.

Design Compromises By Weapon Type

Heavy Machine Guns

Maintaining the full powered rifle cartridges for HMGs was an optimal solution, given they were still primarily used for ranges over 500 m during World War I. Heavy machine guns were a nearly perfectly developed technology by the outset of the war and saw almost no changes in design.1

The scale of issue for HMGs dramatically increased throughout the war. As mentioned in the previous post, the major powers started the war with two per battalion. This is generally increased to four per battalion by 1915 and eight per battalion by 1916. By 1918 the scale of issue varied considerably by Army. As an example, American units averaged about 18 HMGs per battalion.

Light Machine Guns

The ideal LMG criteria would have seen a weapon with a smaller cartridge than the HMG. The trade off of lighter weight and more control was worth the decrease in effective range. However, every LMG adopted during the war used the same full powered cartridge as the HMG.

The three major LMGs used during the war were as follows:

The Chauchat and the MG 08/15 were both hurried conversions that performed somewhere between poorly to marginally adequate. The Lewis gun was an excellent weapon that performed very well.

However, this came at a literal cost. The Lewis gun began the war costing $23,800 per unit in current USD. After a stringent efficiency program the cost was lowered to $8,935 per unit. The Chauchat never cost more than $3,170 in current USD. Consequently the French army produced 2,382 Chauchat’s per division versus the British Empire’s 581 Lewis guns per division.

As good as the Lewis gun was, it was not an ideal LMG. It’s complicated clockwork mechanism required skillful tuning and constant maintenance. It was possible to fire it without the bipod (like in the standing or kneeling position while on the move) but it was virtually uncontrollable due to firing the overpowered .303 cartridge. These overpowered and oversized cartridges were loaded in cumbersome pan magazines that limited the amount of ammunition which could be carried even by a team of two men.

Had the Lewis gun been designed for a smaller cartridge it would have been much more effective at providing mobile suppressive fire for the advancing infantry. However, under the time pressures of war it was not possible to develop a new cartridge and then redesign the 1911 weapon for this new cartridge only to create the logistic headache of supplying multiple types of machine gun ammunition. The same compromise related to time and sharing a cartridge with the HMG applied to all World War One LMGs.

Rifles

The pre-war infantry rifles were poorly suited to trench warfare. They were optimized for firing beyond 400 m in a war where most engagements took place at under 100 m. Its length made moving through a trench difficult and fighting through a trench nearly impossible.

Given the new organization of infantry (which we will discuss later) the average rifleman spent much more time carrying other equipment than fighting with a rifle. To carry equipment into battle the infant year needed to sling his rifle. To move through a narrow trench or avoid getting snagged on a barbed wire the rifle should be slung over one shoulder. However, the rifle then flopped around and could easily fall off.

The rifle could be made more secure by slinging it across the back in the style of the cavalry. This is almost never seen in photos from the trenches as with a diagonal slung rifle soldiers would not be able to fit through the narrow walls of trenches.

The mismatch between standard infantry rifle sights and the conditions in the trenches is the best illustration of the problem. The table below shows the minimum range settings for major service rifles during World War One:

Most rifle shots during World War One took place at under 100 m and only the Russians had a rifle that could be sighted to that range. For 200 m rifles like the Lee-Enfield this meant aiming about 6 inches low, but German infantry with the Gewehr 98 had to aim for the ground in front of the enemy’s feet.

Despite the flaws in pre-war infantry rifles every major power kept the same standard infantry rifle throughout the war.2 What explains this trend of maintaining ineffective weapons?

Firstly, the large majority of ammunition fired and casualties inflicted by firearms during World War I was by HMGs and LMGs. The platoon’s rifles were along for the ride so to speak so they might as well have the same cartridge as the machine guns.

Secondly, every nation struggled to equip the rapidly expanding armies of the conflict. They already had large stocks of prewar rifles and their immediate predecessors in supply.3 Factories were geared up to produce the rifles and their ammunition at a time when assembly-line manufacturing was much less flexible than it is today.

Self Defense Weapons

Ideally members of the infantry manning other weapons (such as machine guns and mortars) would have a short range self defense weapon. This requirement was largely ignored in World War One, apart from German stocked pistols, which are discussed in the next section.

Close Range Firearms

The ideal close range firearm would fire a pistol caliber cartridge with a high rate of fire effective out to about 150 m. Germany was the only major power to implement this type of weapon.

Prior to World War One the German army decided to issue personal defense weapons to troops like artillery that were further in the rear. They adopted two long barreled pistols with detachable shoulder stocks, the the Artillery Luger and the Broom handle Mauser. In 1915 Germany began using special assault units called Stormtroopers. They quickly adopted these stocked pistol carbines as their preferred weapon. During the war Germany manufactured more than 300,000 stocked pistol carbines, but it’s unclear how many were used by the artillery verses Stormtrooper units.

Stocked pistol carbines met the criteria for range and were acceptable for the level of firepower. They were controllable at a high rate of fire due to firing a pistol cartridge on a stocked weapon, but they were short enough to be fired when fighting inside a trench.

The logical next step was to make a fully-automatic pistol carbine with a fixed stock. This led to the development of the first sub-machine gun in the form of the Bergman MP-18.4 The program began in 1915, but by time it was issued the war was almost over. Only about 4,000 saw combat.

The German use of short range weapons illustrates both their promise and limitations. The Stormtroopers were rightly feared for their effectiveness, in no small part for having short range rapid fire weapons. However, full effectiveness required development of a new type of firearm. Even though the Germans began this process within a few months of the war starting they were unable to field the resulting weapon in large numbers before the end of the war.

The German’s inability to develop, produce and issue a new firearm between 1915 and 1918 also shows the decision to keep full powered rifle cartridges for infantry rifles and LMGs was correct.

Other Close Range Weapons

The MP-18 demonstrates that a war is no time to develop a new firearm. On the other hand the last three types of weapons were all developed in 1915 and issued on a mass scale by the end of 1916. These systems (trench mele weapons, grenades and grenade projectors) were not new weapons, but reimagined obsolete weapons.

After the trenches ossified there was no procurement necessary to provide the soldiers with suitable mele weapons. They improvised in some truly sadistic ways.

Beyond the homemade clubs seen above solders used knifes, brass knuckles, mounted bayonets to pistols and sharpened the edges of their hand held shovels.

The other close range weapon to reappear was the grenade. Grenades are older than firearms and saw use in Europe as early as the 15th century. By the end of the 19th century they had fallen out of favor. They had always been almost as dangerous to the thrower as the enemy and long range rifle fire seemed to make them unnecessary.

Once the trench stalemate began field engineers manufactured improvised grenades by packing explosives and rocks into jam tins with a burning wick fuse.

These evolved into more sophisticated models, eventually settling on the iconic mills bomb and stick grenade.

Because grenades were an old technology using fairly simple parts they reached mass manufacture by mid-1915.5

The number of grenades needed to clear a trench system was truly immense. Trenches zigzagged about every 10 m to prevent shrapnel or gunfire going down the length of a trench. Soldiers clearing a trench threw a grenade around every corner prior to rushing, a well as down dugouts, into firing bays, down the entrances to underground bunkers etc.

Consequently by 1915 any soldiers tasked with entering and fighting through enemy trenches carried sacks full of grenades and a close range weapon that could be used one handed (whether it be a trench knife, club or pistol).

The evolution of close range weapons from improvised bodge jobs to mass production withing a year was possible because these weapons were simple and/or resurrected older systems.

Indirect Fire Weapons

When artillery moved into an indirect fire role the infantry lost a great deal of firepower that, while not organic to the infantry battalion, had been co-located on the firing line. The solution was to introduce grenade launchers and mortars within infantry battalions, companies and platoons.

Mortars and artillery are often mistaken for each other. Modern artillery fires shells down a rifled barrel under high pressure. This results in the shell travelling several times the speed of sound on a shallow angle with great accuracy. In World War One Artillery could fire up to about 20 km. The barrel and shell need to be manufactured to precise standards with high quality metals to withstand the high pressures.

Mortars are a much simpler weapon that dates back to the late medieval period. They are smoothbore (they do not have rifling), fire at low pressure and on a steep angle. This results in a short range weapon that comes down almost vertically so that it can drop into a trench. The projectile is called a bomb rather than a shell. Mortars are very simple to construct. The first trench mortars were literally sewage pipes with a block welded to one end.

The modern form of mortar was developed in 1915. They had a range of up to a kilometer or two and were accurate enough at that range. They were mass-produced and widely available by late 1916. After World War I mortars were mostly a platoon, company and battalion level weapon, so they will play a significant role in future posts. However, during World War I they were quickly moved up to brigade and division control.

During World War One indirect firepower at the section and platoon level was provided by grenade launchers. If the mortar was designed to supplement artillery through a low cost, low pressure system with short range then the grenade launcher took this concept to an extreme. Grenade launchers literally began as medieval catapults and crossbows.

One can think of artillery, mortars and grenade launchers being an overlapping continuum in terms of their capabilities and limitations.

Artillery is the Queen of battle due to its overwhelming capability. But as an infanteer it cannot be relied upon. Artillery is centrally controlled, so you may not have priority. It is expensive, so there's never enough. It relies on a complex communication and command system that may be - and in World War 1 usually was - compromised.

Mortars are simpler and cheap enough to be used by platoons and companies. Being this close to the enemy there short range and inaccuracy is irrelevant. If the communications system breaks down the mortar team commander can usually get eyes on the target from a high feature and shout corrections to the mortar crew.

Grenade launchers are just a way of throwing a grenade further than human muscle power. This makes them portable by an individual soldier, and therefore able to be issued down to the platoon and squad level.

By mid-1916 the medieval grenade trebuchets were replaced by rifle grenades. In the decade prior to World War I most armies experimented with rifle grenade launchers. Rifle grenades take a standard infantry rifle with a holder at the muzzle for a grenade projectile. They fire an overcharged blank cartridge to propel the grenade out to about 300 m. Rifles needed to be specially modified to withstand the higher pressure and rifle grenades were fired with the butt on the ground rather than in the shoulder.

The French and Germans also widely utilized rifle grenades. Similar to LMGs a prewar design saw experimentation in early 1915, adoption by mid-1915 and production ramping up enough to see widespread front-line use by mid-1916.

Conclusion

World War I began in August 1914 and was a war of maneuver or until late October 2014. During November to December 2014 the trench networks ossified and it became clear returning to maneuver required new weapons and tactics.

During the winter of 1914 to 1915 the military establishments of the great powers develop the requirements that led to the current weapons and organization of infantry units. In August 1914 the standard infantry battalion was equipped almost entirely with full powered cartridge rifles and it ideally maneuvered at the battalion level. By the end of World War I the infantry platoon (two levels down from the battalion) was equipped with a wide range of weapons and typically maneuvered as a series of platoons.

To enact this multi-weapon platoon armies would ideally adopt the following infantry weapons:

the current HMGs but in much larger numbers;

a LMG for mobile direct firepower in the assault;

a short range out of the way personal defense weapon for soldiers operating crew served weapons;

short range weapons for fighting entrenches, including firearms, grenades and melee weapons; and

indirect fire weapons at the platoon level.

This post examined how the weapons for these requirements were adopted under wartime conditions.

The prewar full powered rifle cartridge was maintained, as was the prewar rifle as the standard infantry weapon. This was not ideal but necessary due to production concerns and the inability to develop new firearms in time for the conflict. As proof of this necessity, the submachine gun was developed as a new firearm during the war but it was not available in significant numbers until the last month of the war.

Almost all the infantry weapons adopted during World War I were either resurrected old weapons types (like maces and grenades) or designs from the decade prior to the war (like LMGs and rifle grenades). Improvised weapons appeared in fall 2014. The formally procured weapons saw experimentation in early 1915, adoption in mid 1915 and production rates high enough to be distributed en-masse to units by mid 1916.

This story of weapons development illustrates how quickly the military establishments of the great powers reacted to the onset of trench warfare. They identified the problem and weapon capabilities needed to solve the problem within a few months. The great powers' industrial base and government procurement bureaucracies were able to mass manufacture these weapons in under a year and a half. Generally speaking the weapons were not refined, but they were good enough and available in large numbers for the decisive years of the war.

However, this is also a story of limitations inherent to technology and warfighting. Despite the war lasting four years, it was fought with hurriedly adopted prewar designs. Design concepts begun during the war arrived too late.

The success of weapons procurement also begs an obvious question: if the armies that fought World War I had a modern set of infantry weapons by the summer of 1916 why did it take until summer 1918 for mobility to return to the Western front?

This leads to the topic of the next post. How tactics, training and platoon organization was modified to utilize the broader selection of infantry weapons.

In 1963 the British Army torture tested their World War I vintage Vickers heavy machine gun by firing 5 million rounds in seven days. This involved a firer, a loader and someone with a shovel to prevent the empty cases from piling up too high on the side of the gun. The machine gun fired without requiring maintenance beyond barrel changes and clearing stoppages. After the test was complete an inspection determined the various pressure bearing parts were still within factory specification.

One caveat being the French army, who went from the Label to the Berthier as the standard infantry rifle. However, the Berthier had been adopted pre war for cavalry and colonial troops.

In the few decades prior to World War I rifle technology had evolved rapidly and great powers tended to replace their rifle about every 10 years. So they had 2 to 3 times as many broadly similar rifles in storage as were in front line usage at the outset of the war.

The Villar Perosa is not a sub-machine gun. Shut up!

Dr. John Sneddon, The Trench Warfare Department 1914-1915 (Western Front Association) March 8, 2017

Not quite the right thread for this question, but it appears Russia's control of airspace has had no practical benefit for them in the Ukraine war. Is the ground attacking, tactical jet aircraft becoming obsolete also?

I try to picture myself in this alien world called WW1. Every time it plays out like a horrific comedy.

“Sarge, I’m not properly trained for knife bat duty. I am certain I will die by this “Lee Enfield” contraption anyways from my own rifle.

I’ll sacrifice my rations for the week as punishment”

“Private, give me your rations. Your on knife bat duty until we are relieved in 3 months”

To think WW1 was endured and we were right back at it.

“The life of man upon the earth is warfare, and he is born to trouble, as surely as the sparks fly upward.’”— Job 5,7

Another great article!