Let's Invade Iran Part 3

US Strategy and Force Ratios

In the last part we examined the Iranian military, and how it it geared towards a hybrid hedgehog defence. The conventional military would withdraw to a national redoubt based on the mountainous part of the country. This would preserve the majority of Iran’s territory and population, but it would mean giving up most of her oil fields. An air defence system would hopefully prevent US air power from being decisive, while missile strikes, insurgency activity, drones and cyber attacks on US controlled areas would erode American resolve.

In this part we will look at what US planners would see as the required invasion force, and the American capacity to deploy that invasion force to the region.

Misuse of the 3:1 Ratio Rule

Commentators cite the 3:1 Ratio rule to a shocking extent when looking at warfare on an operational or strategic level. This rule states that: to be successful an attacking force should be 3x the size of the defending force.

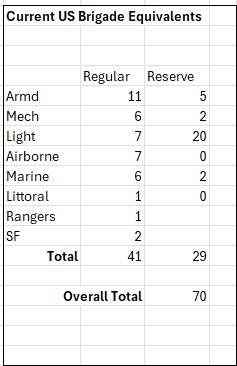

Applying this oversimplified understanding of the 3:1 Ratio rule to Iran’s military leads to some comical conclusions. Assuming Iran has 81 combat brigades then according to the 3:1 ratio the US would need 243 combat brigades to successfully invade Iran. This is over three times the size of the entire US armed forces (at 70 combat brigade equivalents) and only slightly less than the US armed forces during world war two (at 285 combat brigade equivalents).

As covered in a previous video, the 3:1 force ratio for an attacker is a misunderstood rule of thumb from the tactical level. A hypothetical US invasion of Iran is a good example of why it often does not apply.

Instead the 3:1 ratio:

Is a rule of thumb for the point of engagement at the tactical level;1

On an operational to strategic level a ratio of 1.3:1 is normally enough to succeed; and

The ratio is not based on the number of soldiers, but on relative combat power. So an attacking company with 3x the combat power (say because they are better trained, better equipped and have better artillery support) can defeat a defending company.

So what is a proper application of the 3:1 Ratio Rule as it applies to a US Invasion of Iran?

Refining the Math for the 1.3:1 Ratio

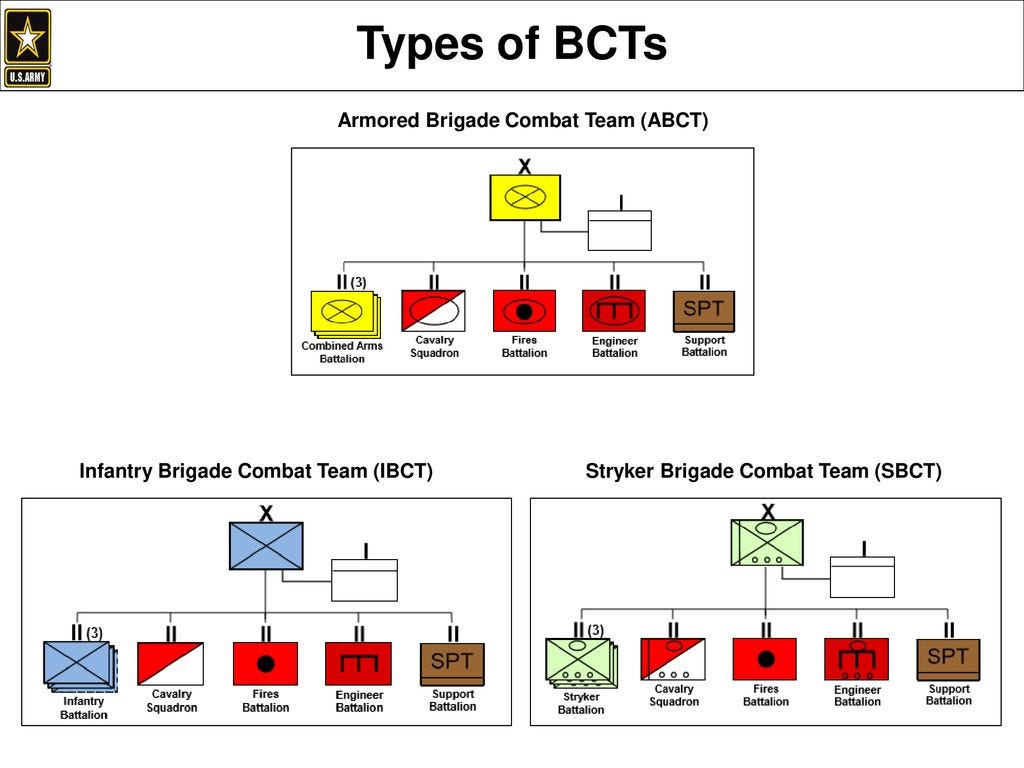

As mentioned in the previous part, Iranian combat brigades are built on the eastern model, which are slightly more than 1/2 the size of the western model of brigades. A US Brigade Combat Team is approximately 4,000 to 4,700 soldiers. Iran claims to have brigades with 3,000 to 5,000 soldiers, but looking at the size of their military these units would probably be at 75% strength versus US BCTs, which are held at over 95% strength.

This doesn’t capture the larger size of US divisional, corps and army level assets. The US Army has 954,875 total uniformed personnel organized into 62 combat brigades, for what’s called a brigade slice of 15,401 soldiers. Iran has 890,000 ground personnel in 81 brigades, for a brigade slice of 10,987. Therefore before even looking at the quality of training, equipment and logistic support an Iranian brigade is worth approximately 2/3rds of a US military brigade.

Therefore in sheer numbers, Iran’s 81 combat brigades would be the equivalent size to 54 US brigades. If we apply the 1.3:1 ratio for the operational and strategic level this would require the US needs about 70 brigades for a successful invasion of Iran.

The US Military’s Size

By an odd coincidence, 70 is exactly the number of combat brigades in the US military, assuming a full mobilization of the National Guard and with the USMC’s units added.

The US military would need to retain at least a third of these brigades for home defence, a strategic reserve and for other overseas commitments. So on a numbers only analysis of the 1.3:1 ratio the US military can’t invade Iran without at least 24 brigades contributed by allies. Given the US’ most reliably ally would struggle to provide more than 4 combat brigades this is a tough ask.

This exposes an interesting dynamic in US military power, thought they have the world’s largest military budget they have a somewhat unremarkable number of combat brigades.

A good comparison is the South Korean military. They use the western brigade structure and are a highly developed country with a similar cost of living. South Korea’s military has 76 combat brigades. Adjusting for South Korea having slightly smaller brigades, their army is the numerical equivalent to 67 US BCTs, only three less than the US military. South Korea fields this comparable ground force with approximately half as many uniformed personnel and 6.6% the US military budget.2

Why the US Military is So Expensive for its Size

However, this isn’t a rant about graft and inefficiency in the US military industrial complex.3 The US military has a tiny number of combat brigades compared to it’s budget because it has a unique mission requiring unique (and staggeringly expensive) capabilities.

Miltaries around the world generally fall into two categories: large armies designed around defending their own borders and small armies designed around expeditionary warfare. South Korea’s military exists solely (one might say Soel-ly)4 to defend against an invasion by North Korea. France has about the same military budget as South Korea, but has 16 combat brigades versus South Korea’s 67. However, France can deploy and sustain a few brigades anywhere in the world. South Korea cannot.

There is a short list of expeditionary warfare armies that can sustain a brigade anywhere in the world long term.5 Only three expeditionary armies that can deploy 2-4 brigades anywhere in the world, including providing their own carrier based air support and amphibious landing capability. Namely Britain, France and maybe Japan.

America has the only expeditionary military that can deploy 5 or more combat brigades overseas. But she can deploy dozens of brigades. The gap in capability for expeditionary warfare is staggering. Maintaining this staggering gap requires a staggering amount of money.

As an example, a critical asset for supporting overseas deployments is a heavy strategic lift aircraft. The best one is the C-17 Globermaster III, which costs $340 million per air-frame and has $30,000 per hour in operating costs. There are only six countries in the world with heavy strategic lift aircraft and the ability to deploy at least a brigade overseas. Below is a list of the 2-6th ranked countries.

The US military has 222 C-17 Globemaster IIIs………. I feel like I need to say that again, because there’s no way it had sufficient impact the first time. The US military has 20x the heavy strategic lift aircraft of the #2 nation.

So at the cost of a trillion dollar military budget the US can project power on a scale unlike any other nation, but in boots on the ground numbers they are comparable to a half dozen countries that spend a fraction as much on defence.

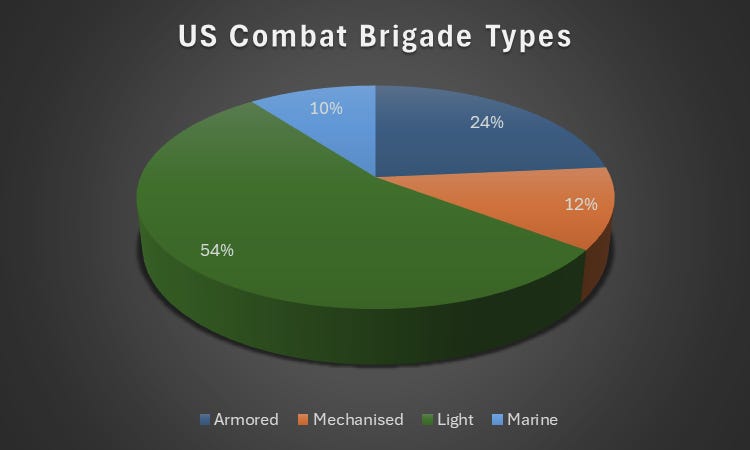

The US Military’s Force Composition

America’s expeditionary military is also reflected in their force composition. Light infantry units6 of various types make up 54% of US combat brigades. These units are well suited to complex terrain (like jungles and mountains) and counter-insurgency warfare. Light units are also much easier to logistically support overseas. In very rough terms light units consume about 1/2 the weight of supplies as heavy units. Light units can also be moved into theatre by air.7

Armoured and Mechanized units are better suited to open terrain and conventional warfare. These units only make up 36% of US combat brigades.

This means the US military is currently not optimized to fight conventional warfare, unless they are fighting on complex terrain. Fortunately, Iran as a mountainous country is full of complex terrain.8

Understanding Combat Power through Historical Examples

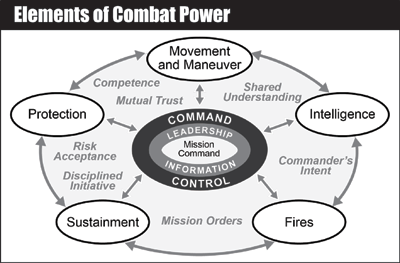

The final problem with the 3:1 ratio is that it isn’t a measure of the size of units, but of their combat power. Think of combat power as a number representing that unit’s ability to visit destruction on the enemy. So a militia company has less combat power than elite light infantry, and elite light infantry has less combat power than an armoured company.

Staff officers have access to combat power estimate tables that are painstakingly assembled over decades. They are all classified. The limited information I recall is out of date and I can’t discuss it without risking going to prison.

Instead I will attempt to approximate the combat power ratio needed for a US invasion of Iran through the historical data from the 1991 and 2003 US operations against Iraq. These operations had a similar technology gap to an invasion of Iran. We also know from the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq war that these armies were roughly similar in quality. On the other hand, Iran has a better air defence system and better defensive terrain; so the combat power ratios from this analysis should be taken with a grain of salt.

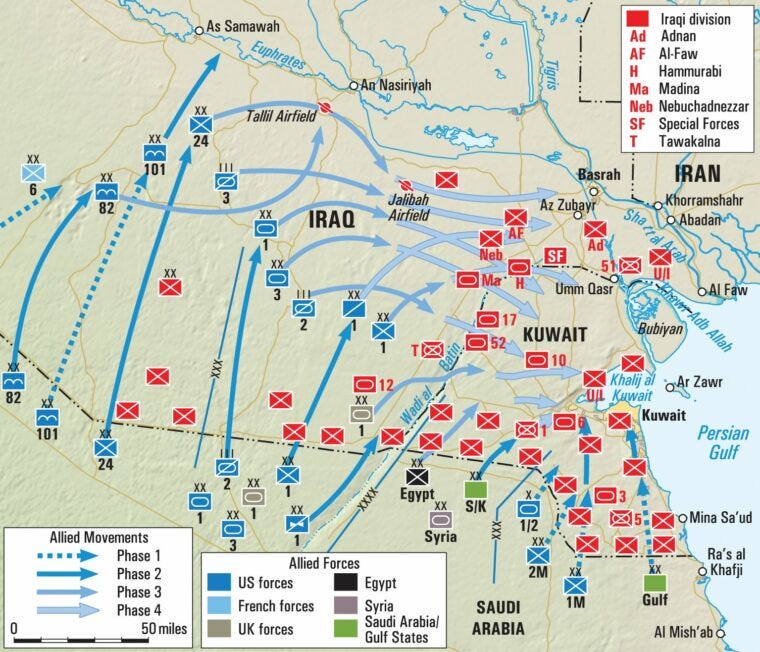

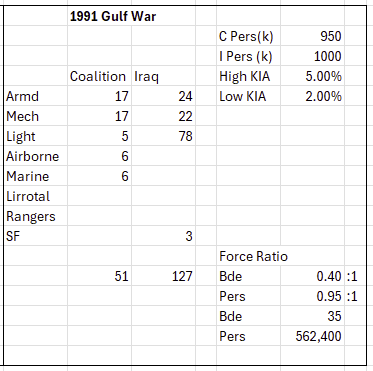

Desert Storm 1991

During Desert Storm in 1991 the US assembled a coalition with 51 combat brigades versus 127 Iraqi combat brigades. However, the Iraqi brigades were much smaller and the two sides had a manpower ratio of 1 Iraqi to 0.95 coalition solders. The Coalition had about twice as many armoured or mechanized brigades (34% vs 66%). Crucially, the US Coalition had air supremacy and spent 5 weeks leading up to the ground campaign mangling the Iraqi army.

The ground campaign lasted 100 hours. Although there’s a historical memory of the Iraqi army capitulating rather than fighting, they suffered casualties of 2-5% of the total force killed in action. This suggests the combat brigades in contact with the Coalition suffered near annihilation levels of casualties.

We can conclude that in 1991 a military that was qualitatively similar to Iran’s was quickly destroyed by a US Coalition with air supremacy. They accomplished this with a force ratio of 1 to 0.4 in brigades and 1 to 0.95 in personnel.

Applying these combat power numbers to Iran’s army the US would need an invasion force of 562,400 personnel organized into 35 brigades.

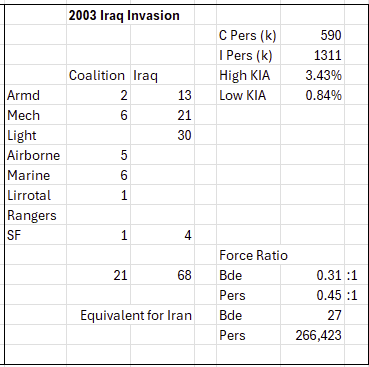

2003 Invasion

In the 2003 invasion the US Coalition was much smaller. The Iraqi army was reported as larger (1.3 million versus 1 million in 1991), but these numbers appear to be inflated as they fielded approximately half as many brigades (68 versus 127 in 1991).

In the 12 years since Operation Desert Storm the technology gap had increased significantly. The lower Iraqi killed in action percentage of 0.8-3.4% also suggests this time the media perception of the Iraqi army not having the motivation to fight was more accurate than in 1991.

We can conclude that in 2003 a poorly motivated military that was inferior to Iran’s was quickly destroyed by a US Coalition with air supremacy. They accomplished this with a force ratio of 1 to 0.31 in brigades and 1 to 0.45 in personnel.

Applying these combat power numbers to Iran’s army the US would need an invasion force of 266,423 personnel organized into 27 brigades.

Estimating the Required US Invasion Force

Using the historic examples of the 1991 and 2003 operations against Iraq, the US needs 35 to 27 combat brigades for a successful invasion of Iran. For that invasion they also cannot count on more than 5 combat brigades from allies.9 This means the US military needs to provide 22-30 combat brigades for a successful invasion of Iran. This is within the US military’s capabilities, but it would require a mobilization at a level not seen since WW2.

At a minimum the bulk of the National Guard would need to be called to active service. During the 2003 invasion of Iraq 16 of the 21 combat brigades were American.10 This is probably the maximum capability of the US Army today without a widespread mobilization of the National Guard; which had less than 9,000 guardsmen for the initial invasion.

Since 2003 the US army has contracted by about 10%11. The US Army today has less overseas commitments, but they are also less flexible. In 2003 they had 9 combat brigades stationed in Europe and South Korea, versus 6 today. However, during the War on Terror the European and South Korean stationed units were rotated at will through Iraq and Afghanistan. This is no longer possible, especially for the 5 brigades in Europe.

During the War on Terror National Guard and Army Reserve mobilization peaked in 2004 at 156,000 or about 27%. This enabled the US Army to deploy 6 additional combat brigades overseas. Therefore to assemble an invasion force of 22-30 combat brigades a minimum of 50% of the National Guard and Army Reserve would need to be called up to active duty, almost doubling the mobilization at the peak of the War on Terror.

Conclusion

According to the 3:1 rule the US military would need 243 combat brigades to successfully invade Iran. This illustrates that the often cited 3:1 rule is useless at the operational level.

Applying proper operational level analysis, assuming 1991s Operation Desert Storm as a comparison for Iran’s combat power, and assuming up to 5 allied brigades, the US needs an invasion force of 22-30 combat brigades.

The current US military is capable - but just by the skin of its teeth - of assembling this force of 30 combat brigades while maintaining its other core overseas commitments. The US military is also better built for a war with Iran than for its other two rivals, Russia and China.

However, to assemble a force large enough to invade Iran America needs to mobilize the National Guard and Army Reserve at more than twice peak War on Terror levels. This would be politically very unpopular, and would probably require an instigating event more serious than 911. However, I will leave political speculation to more informed commentators.

In the next part I will look at how the US might utilize this invasion force of 27-35 combat brigades by conducting terrain analysis for the possible invasion routes out of Turkey, Iraq and the Persian Gulf.

As an example how this plays out: If each side needs 10 brigades to cover the front line then the army with 12 brigades can concentrate a 3:1 advantage locally against an army with 10 brigades.

South Korea’s army had 67 combat brigades and 420,000 personnel. They also have a Marine force of 29,000 in 9 combat brigades. Their 2022 military budget was $65.1 billion USD versus America’s $987 billion USD.

American readers may be shocked to discover that internationally US military procurement is seen as a model of (relative) efficiency and effectiveness. For example, Canada is about to spend as much on their new frigates as the US Navy spends on an amphibious assault ship (what the rest of the world would call a light aircraft carrier). This more in line with the western norm for defence procurement.

Badump-Tis

This list probably consists of Canada, Australia, Germany and Italy.

Light infantry, airborne, air-mobile and special forces.

Thought it is technically possible to move an armoured brigade by air, the number of flights make it not worth the effort.

This means the US military’s current organization is not well suited to fighting conventional opponents without lot of complex terrain, like Russia and China.

During Operation Desert Storm in 1991 29 of 51 combat brigades were American, but this was when the US army was almost twice its current size.

In 2003 the US Army totalled 1.06 million including the national guard. Today it totals 955,000.

Currently the British army can deploy a division of three brigades and Australia can deploy a brigade. It is unlikely any other nation would contribute a full brigade.

Great analysis. One omission though is where to get the sealift to run the logistics of operating the equivalent of the entire US military in Iran. That may well be the biggest Achilles heel.

Due to Iran's rugged terrain, they rely on a relatively small number of transit chokepoints, if these are severed it will greatly complicate their ability to move supplies and manpower around. Worth doing an analysis of this. It features strongly in the US militaries war plans for any potential conflict with Iran

Simplicius did a good write up of the Iraq war myth

https://open.substack.com/pub/simplicius76/p/the-iraq-war-was-a-sham