In the last post we examined how the lessons of 1914 led to infantry units moving from almost exclusively armed with magazine fed full cartridge rifles to a broad set of weapons. The weapons were largely adopted in 1915-16 and began reaching front line units in large numbers in 1916-17.

However, procuring weapons is a relatively small part of the puzzle compared to the tactics and training to ensure those weapons are used effectively. In this post we will look at what occurred between early 1915 to late 1916 as the new infantry platoon tactics and organization began to take shape.

Tactical Learning in 1915

Most of the improvements in tactics in 1915 focused on improving trenches and artillery. Within a remarkably short period of time very detailed pamphlets were circulated regarding all aspects of constructing trenches, barbed wire, gas warfare defence and trench raids.

The French army was probably the biggest innovator of 1915. The British and German armies focused most of their efforts in late 1914 and early 1915 on mastering the details of trench warfare. As an example, about once a month the British Army circulated lengthy documents detailing best practices for trench layouts, engineering works, trench raids and so forth.

The French army started World War I with probably the worst tactics and doctrine of the great powers. They still preferred advancing on closed order with 1 m spacing rather than open order on 3 m spacing like the German and British armies. However, in 1915 General Ferdinand Foch led major reforms including firing the majority of generals at the rank of colonel and above.

In April 1915 French army released a new doctrine for offensive operations But et conditions d’une action offensive d’ensemble (in English Goal and Conditions for a General Offensive Action) generally abbreviated as Note 5779. This document introduced three points of great historical significance:

The use of creeping barrages by the advancing force. A creeping garage is when artillery lays down a wall of shrapnel that moves forward at a walking pace in front of the advancing infantry. The goal is to force defending infantry into underground bunkers where they cannot fire on the advancing attackers. The advancing infantry cannot get too close to the creeping garage or they will begin taking casualties from friendly fire. However, if they lag too far behind the creeping garage the enemy will have time to exit their bunkers and fire on the advancing infantry. This dynamic became known as the race to the parapet.

An embryonic form of storm trooper tactics where the first wave advances on a narrow front deep into the enemy trench network while bypassing resistance.

Specially equipped trench clearing troops in the second wave. These soldiers would be equipped with melee weapons, pistols and grenades. Unlike the first wave who would jump over the trenches to continue the advancing depth the second wave soldiers would systematically route out enemies who remained in trenches and bunkers.

Note 5779 was a foretaste of things to come and resulted in the French initially having enormous success at the second Battle of Artois in May 2015. However, it had very little to say about how infantry operates at the battalion down to platoon level. Mostly addressed artillery fire planning and how divisions should commit regiments and battalions to an assault. Furthermore, the new infantry tactics required the range of new weapons discussed in the previous post to be effective.

The Revolution in Tactics of 1916 (The Somme: A Case Study)

I will use the Battle of the Somme as a case study in how infantry platoon tactics and organization was revolutionized during the course of 1916. Similar revolutions took place in the German, French and to a lesser extent Russian and Austro-Hungarian armies around the same time. However, the British army is the best case study because it was, in modern gamer parlance, a speedrun.

At the beginning of the Battle of the Somme on July1, 1916 the British Expeditionary Force (“BEF”) reverted to an older form of infantry tactics (closer to the Crimean War of 1853-56). When the battle ended four and a half months later the BEF’s infantry platoon tactics and organization were broadly the same as today’s.

The Somme: Planning and Pre-Battle Circumstances

The battle of the Somme is one of the most misunderstood and misrepresented events in modern history. Explaining this will eventually take up an entire video series. However, the brief facts are as follows:

Between the 1901-1915 British infantry advanced through a system of fire and movement. This was the major lessons learned during the Boer war. Infantry would spread out 3 to 5 m apart, the first group shoot while prone or kneeling to keep the enemy’s heads down while the second group ran forward in a short rush. The second group would then shoot while the first group rush forward. This was colloquially known as pepper potting, due to its tendency to be demonstrated with salt and pepper shakers on a mess table.

During a number of offensives in 1915 the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) nearly broke through German trench positions. In the process they learned an attack was generally successful if they fired more than 40,000 shells per attacking division. However, the 1915 offensives wiped out the last remnants of the highly trained prewar regular Army.

General Douglas Hiag started 1916 with an army mostly made out of recruits from the beginning of the war. He assessed they were not well-trained enough for fire and movement tactics. He recommended the BEF spend 1916 on the defensive focusing on training.

General Haig was overruled for political reasons. The compromise was a French offensive at the Somme with British support as the junior partner to start on July 1, 1916.

Throughout spring 2016 the French army was suffering a monumental struggle at Verdun. Consequently, the Somme offensive went from the French in the lead with British support to the other way around.

General Haig solution to his poorly trained infantry was to use artillery in place of rifle fire as a means of suppressing the enemy while they crossed no man’s land. Since fire and movement was not possible with these raw recruits they would march forward in a steady advance.

To counteract the infantry’s increased vulnerability General Haig allocated about 3.5x the shell density that had proved necessary in the 1915 offensives.

On paper this should have worked, and it probably would have worked against the German trench network of 1915. However, the German trench network of 1916 was much more resistant to damage from artillery.

The First Day of the Somme (A False Memory)

The popular image of what occurred at the opening of the Somme offensive on July 1, 1916 is of waves of men marching slowly to their death to no noticeable effect on the enemy. The soldiers were weighed down with about 66 lbs of equipment each, and so were sitting ducks. The BEF took almost 60,000 casualties that day while achieving almost nothing. This madness continued for another 4 ½ months with nothing of consequence being achieved.

July 1, 1916 is the definitive public memory of World War I. It was certainly a disastrous day and saw the highest single day casualties in British military history.

“Would this brilliant plan involve us climbing out of our trenches and walking very slowly towards the enemy sir?”

Captain Blackadder in 1917 saying something that was only true for 1 day in 1916.

However, let’s consider a few facts about July 1, 2016 that run contrary to public memory:

It was a fairly hot sunny day. Northern France is the more temperate part of the country, but after all this was July. There had been some light rain fall earlier in the week, and the offensive was delayed to allow the ground to firm up. The high temperature on July 1 was 26C (79F). This means the July 1, 1916 attack did not involve mud. Pictures from the time show grassy fields and dry earth.

The BEF’s casualties for the day were very high, but do not align with the popular memory of total slaughter:

Based on the number of infantry battalions involved approximately 141,686 to 124,800 BEF soldiers went over the top on July 1st;

Of these 38,230 were wounded and 19,240 killed;

This means 13.6-15.4% percent of those who went over the top were killed, 27-30.6% were wounded and 59.4-54 % survived the day unharmed; and

This is certainly a horrifying set of statistics, but I would bet good money that most people think the rate of killed and wounded was much higher.

The first day involved 11 British and 2 French divisions. Four of them achieved their first day objectives (the 2 French and 2 British divisions in the south). Another 3-4 captured almost half their objectives. Generally speaking the Allies were successful in the South, partially successful in the centre and made no impact in the North.

The point about soldiers being weighed down with 66 lbs of equipment has always struck me as particularly ridiculous. By the standards of the rest of World War I this was slightly below average. By modern standards it’s an incredibly light load for an assault. To assault a German trench and survive the inevitable counterattack requires a lot of heavy equipment.

In terms of selective memory or cultural conception of the first day of the Somme only really applies to the northern third of the offensive’s frontage. This cultural memory also has a higher casualty rate than occurred and ignores the reasons General Haig developed what seemed like a good plan (artillery suppression) for a battle he was only fighting against his better judgment.

Why the Rest of the Battle of the Somme is Ignored

It is important that the cultural memory of the battle of the Somme ends on July 1, 1916 with a statement that despite the disaster this senseless offensive ground on for another 4 ½ months. One is left with the impression that marching slowly towards German machine guns to no effect continued into mid-November.

This comment is usually buttressed by a photo of soldiers slogging through a muddy morass and a map showing the battle ended with the BEF having only advanced about 5 miles. The implication being that nothing changed as callous Generals threw troops against German machine guns to no effect.

However, if we compare the casualty exchange ratio for July 1, 1916 to the remainder of the Somme offensive we find a tale of two battles. The Casualty exchange ratio is simply how many casualties you inflict on the enemy for each casualty you suffer. It is generally regarded as the best measurement of the relative effectiveness of military units.

On July 1st the Germans suffered 6,226-12,000 casualties, for a casualty exchange ratio of 0.1 - 0.2 : 1.1 This means the Germans had 0.1 to 0.2 casualties for each Entente casualty. The Entente casualty ratio on the western front through the war was about 0.7 : 1, so the July 1st attack was a very poor showing indeed.

However, if we exclude the July 1st casualties the BEF performed very well in terms of casualty exchange ratio for the rest of the Battle of the Somme.

For the rest of July the BEF achieved inflicted approximately the western front average casualty exchange ratio. In August it peaked at 0.88 - 1.22 : 1. In September through November the BEF’s logistics system collapsed and worsening weather made advancing more difficult. However, they still achieved around a 0.9 : 1 ratio under those conditions.

So if we exclude July 1st (which granted is a huge if) the BEF inflicted nearly as many casualties on the offensive against a more experienced and better trained German army on the defensive.

It is hard to overstate the impressiveness of this casualty exchange rate or how dramatically the BEF improved in a short time.

So what occurred between July and November 1916 to transform the BEF from a force suffering a casualty exchange ratio possibly as low at 0.1 : 1 to near tactical parity with the German army? The answer is a revolution in the organization and tactics of the infantry platoon.

The Revolution in Organization and Tactics

A detailed explanation of how the BEF revolutionized infantry platoon organization and tactics will need to be covered in the nest post. However, the BEF spent the winter of 1916-17 codifying how it adapted after July 1st on the Somme into the pamphlet SS 143: Instructions for the Training of Platoons for Offensive Action2

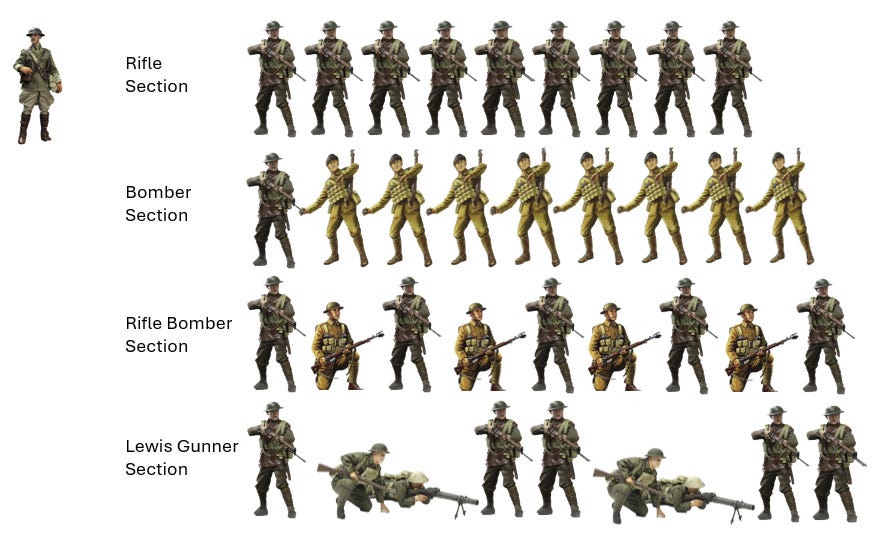

The infantry platoon prior to the Somme battle consisted of four sections of riflemen, with all other weapons types held at company level or higher.

SS 143 gave a specialist role to each section, enabling each platoon to fight as a miniature army.

The roles of each section were as follows:

Bombers: Fight through trenches with hand grenades, pistols and malee weapons.

Lewis Gunners: Suppress the enemy (keep their heads down so you can manoeuvre) with direct fire.

Rifle Bombers: Suppress the enemy with indirect fire. SS 143 actually refers to them as the “howitzers of the infantry”.

Riflemen: A general purpose section. They can assault or gain fire superiority like the Lewis and Rifle Bomber sections (though not as well). They have grenades (though not as many as the bomber section). They also act as the platoon’s scouts and flank security.

The overall offensive tactics of the rifle platoon were for the Lewis gun and Rifle Bomber section to suppress the enemy, while the Rifle and Bomber sections flanked the enemy and cleared the enemy from their trenches.

The overall approach of one unit suppressing the enemy while another manoeuvres to a flank and destroys them goes back to Alexander the Great. However, prior to 1916 the manoeuvring occurred at battalion or brigade level (two to three levels above the platoon), while supporting indirect fire occurred at brigade or division level (three to four levels above the platoon).

The next post will look in more detail at how this platoon sized mini-army fought, what roles were still handled by higher levels and the training problems this created.

German casualty estimates for the Battle of the Somme are highly variable and make it difficult to find precise casualty exchange ratios.

S.S. 143, Issued by the General Staff, February 1917. http://www.kingsownmuseum.com/ko2147-02.htm.

Interesting genesis of small unit tactics - I wonder how well co-ordinated they were with division level artillery, and were these developments matched by innovations in communications and battlefield awareness? How long did First World War armies have to wait for improvements in ‘combined arms’ doctrines to materialise?

One legacy of the four-section rifle platoon is that the fire-teams in rifle sections are still ‘Charlie’ and ‘Delta’: the third and fourth in the order of battle, and those which remain after the bombers and machine gunners (‘Alpha’ and ‘Bravo’) were later detached and collected in support company.

Fascinating analysis, the casualty ratios from 1 Jul onwards are a real marker of how effective evolving doctrine can be. Thank you.